Scroll

femisphere.co.nz

Thanks to:

Femisphere 4

Colophon

femisphere.co.nz

This issue was made possible thanks to a Creative New Zealand Suffragette 125 Fund

Front and back cover art: Sriwhana Spong,

Tasseograghy of a Rats Nest (extended), 2018

Design and development: Eva Charlton, evacharlton.com

Proof reading: Marie Shannon

Femisphere is compiled by Judy Darragh and Imogen Taylor

Typefaces: Laica A Medium and Whyte Book

Thanks to:

All of our current, past and future contributors

Roxanne Hawthorne

Creative New Zealand

Strange Haven

Enjoy Contemporary Artspace

The Physics Room

Blue Oyster Art Project Space

Get in touch with us:

Email: femispherepublication@gmail.com

Instagram:@femispherezine

Facebook:@femispherenz

Femisphere 4

Biographies

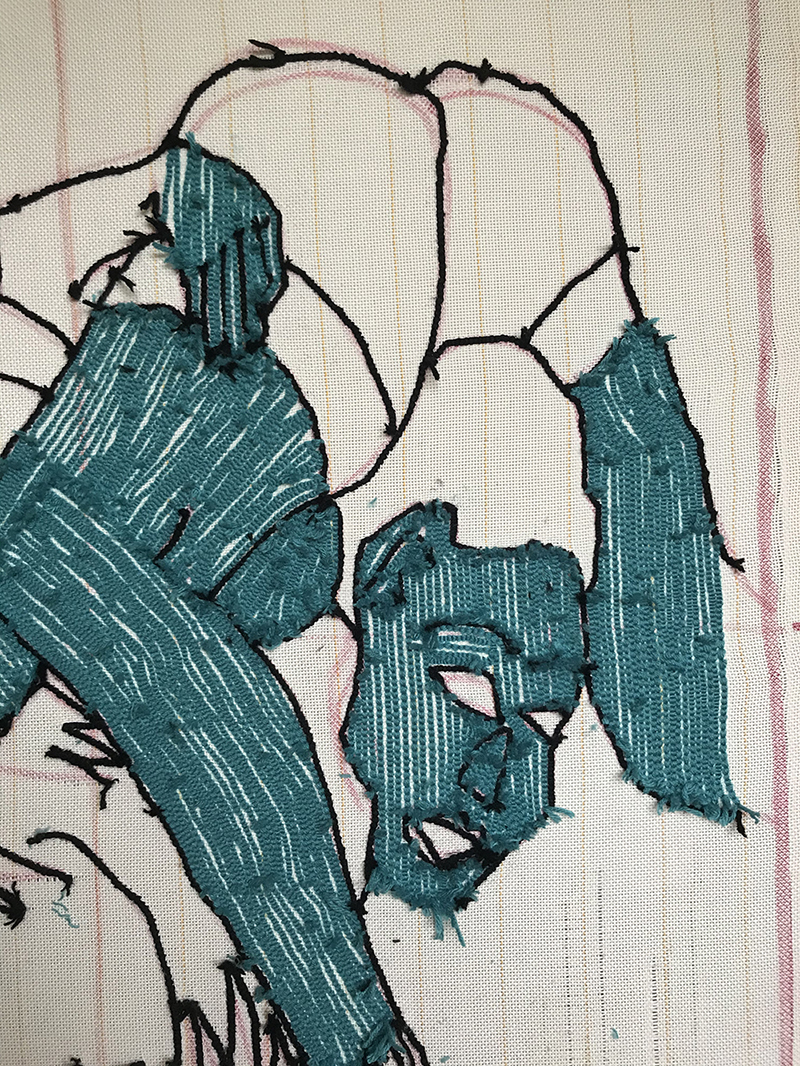

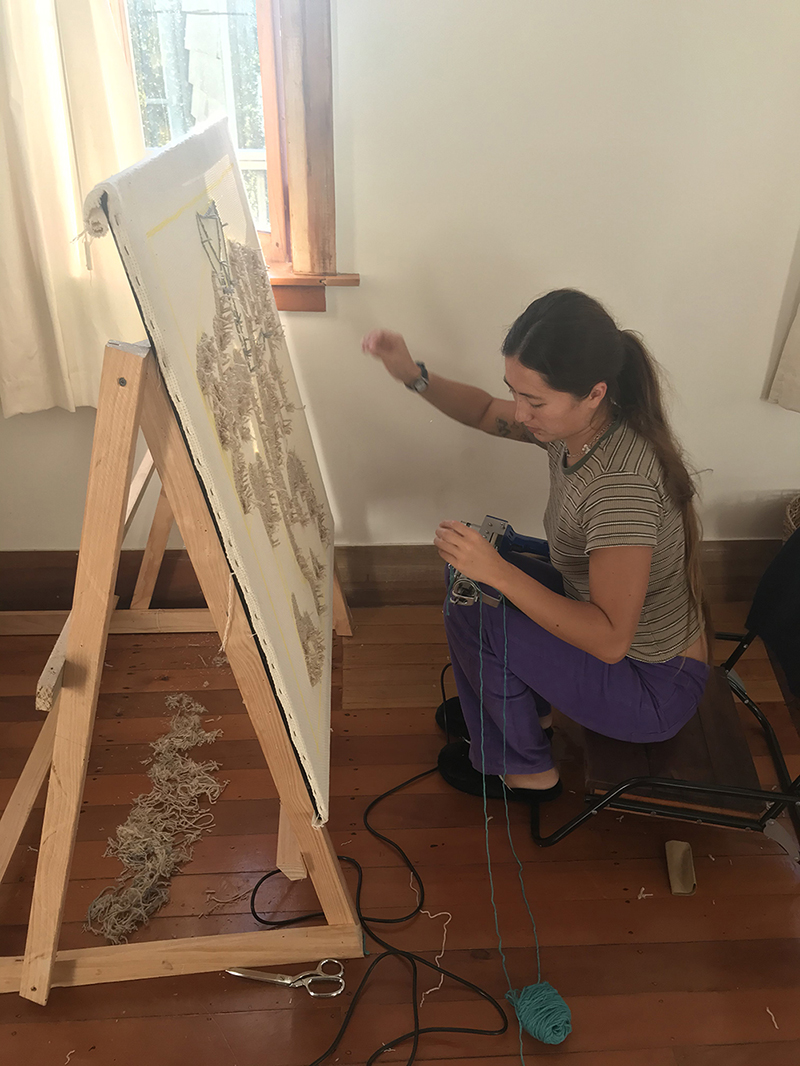

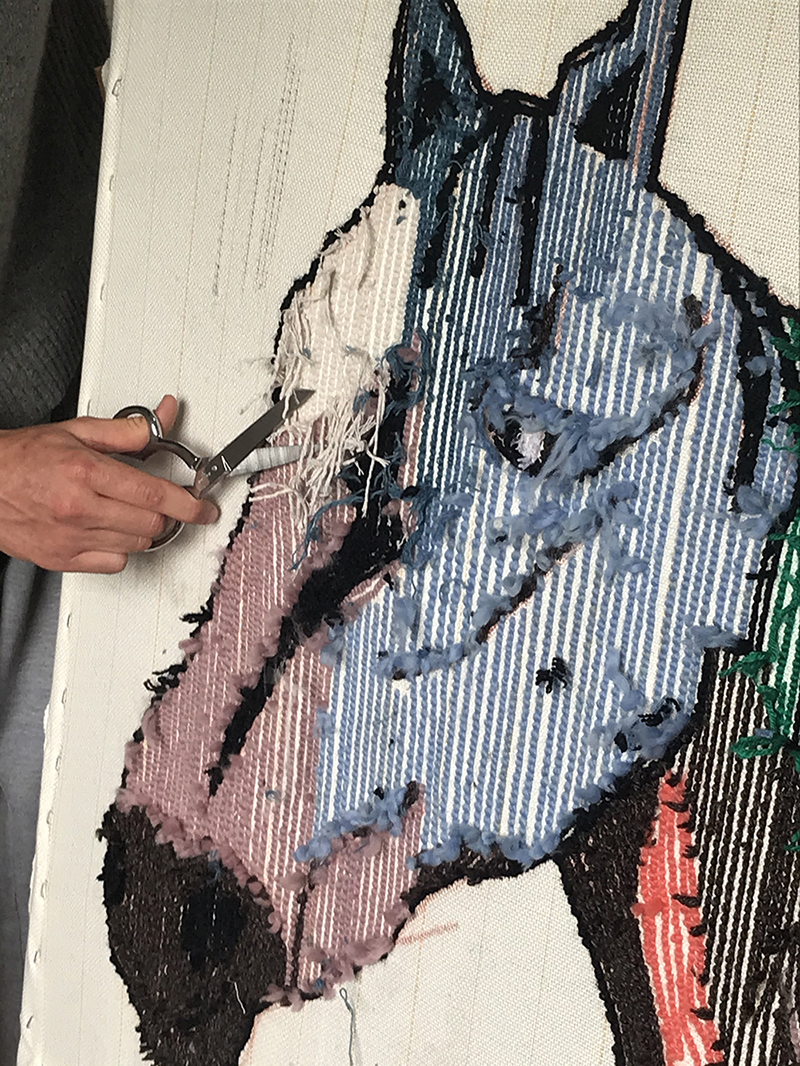

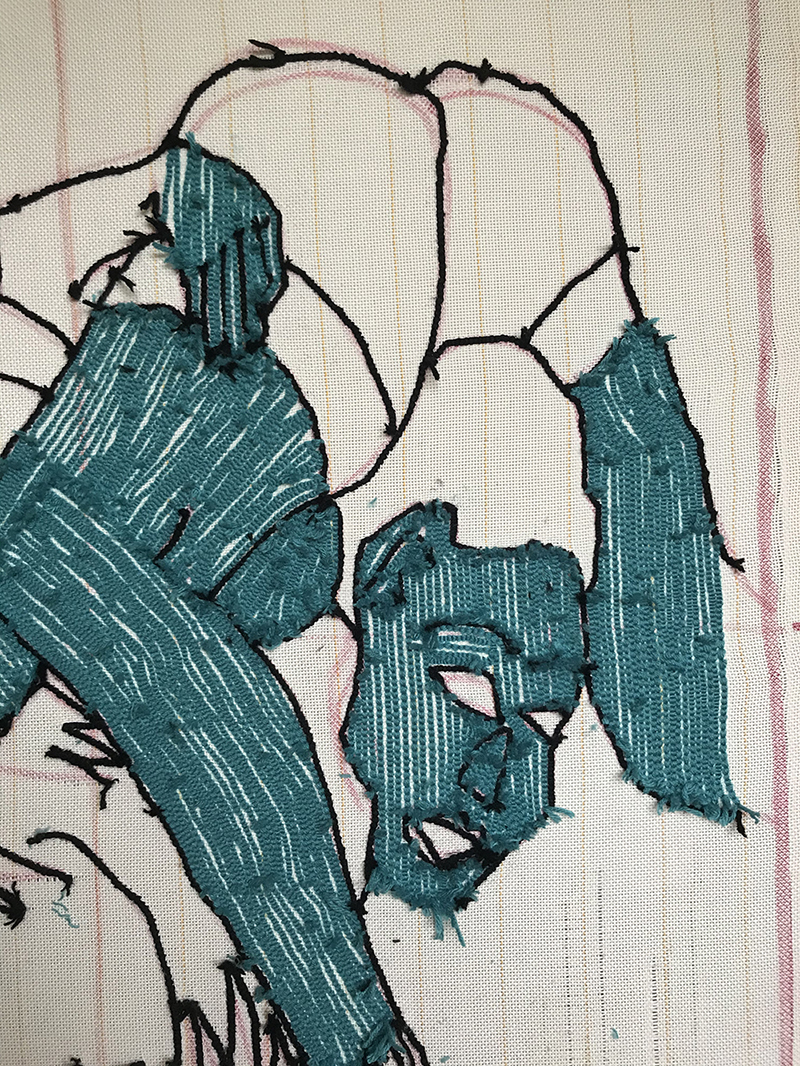

Alice Alva is a multi-disciplinary artist and art educator based in Te-Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, New Zealand, who works across drawing and illustration, embroidery and textiles, painting and graphic design. Her work is situated at the intersection between art and craft and the act of making. Alice has exhibited her work across Australia and New Zealand, including at the Wallace Gallery, Toi Pōneke, RM Gallery and Dunedin Public Art Gallery’s Rear Window Project. She was a finalist in the 27th Annual Wallace Art Award and the Parkin Drawing Prize 2018.

www.alicealva.com Instagram @glassandbones

Greta Anderson (b. Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand) completed a Master of Visual Arts Degree at Sydney College of the Arts in New South Wales (2006) and a Bachelor of Fine Arts at Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland (1999). Atmospheric and visually striking, Anderson’s draws cinematic qualities into her still photographic images, embuing them with mood and drama. Anderson often captures figures and objects in intermediary states, moving from day into night, stillness into potential. Her notable solo exhibition The Stand Ins was held at Te Tuhi, Pakuranga, Auckland (2003) and she has since been the recipient of several grants and awards. Anderson has been selected for numerous major exhibitions at important venues for contemporary art and photography including Gus Fisher Gallery (Auckland), the Australian Centre of Photography (Sydney), The University of Sydney, the Museum of Photographic Arts (San Diego), the Ringling Museum of Art (Sarasota) and the Archibald Prize at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (Sydney).

Anderson’s work has been featured in numerous photographic compendiums including Picturing Eden by Anthony Bannon and Deborah Klochko (2006), Future Images by Mario Cresci (2010), PhotoForum at 40: Counterculture, Clusters, and Debate in New Zealand by Nina Seja (2014), and See What I Can See: New Zealand Photography for the Young and Curious by Gregory O’Brien (2015). In addition, Anderson has a comprehensive commercial portfolio, having been invited to photograph campaigns for high-profile advertising agencies including Saatchi & Saatchi, DDB, and Mojo, and for editorials in the New Zealand Herald, Metro Magazine and the Australian Financial Review.

www.gretaanderson.com

Hana Pera Aoake (Ngaati Hinerangi, Ngaati Mahuta, Tainui/Waikato) is an artist and writer based in Waikouaiti on stolen Waitaha, Kaai Tahu and Kaati Mamoe whenua.

Grace Bader is a practising artist based in Auckland, New Zealand. Observing relationships between line and shape, her work plays with abstraction and the human figure. The idea of connection is central to her practice. She says, “I paint because I have to; it makes me feel. To feel is to be alive.” Grace is represented by Melanie Roger Gallery.

www.melanierogergallery.com www.gracebader.com Instagram @grace.bader

Gemma Banks is an Ōtautahi-born artist, designer and arts administrator. She graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts (First Class Honours) in Graphic Design. During her study she interned at Ilam Press, designing and printing artist’s books. From there she worked in-house at the Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. She has been involved in designing and Risograph printing a number of award-winning poetry books for Canterbury University Press and has recently been published in Share/Cheat/Unite and Hamster. She was nominated as a finalist in the AGDA Awards 2019 and the DINZ Best Awards 2019 for her work on Heart of Glass for Enjoy Contemporary Art Space.

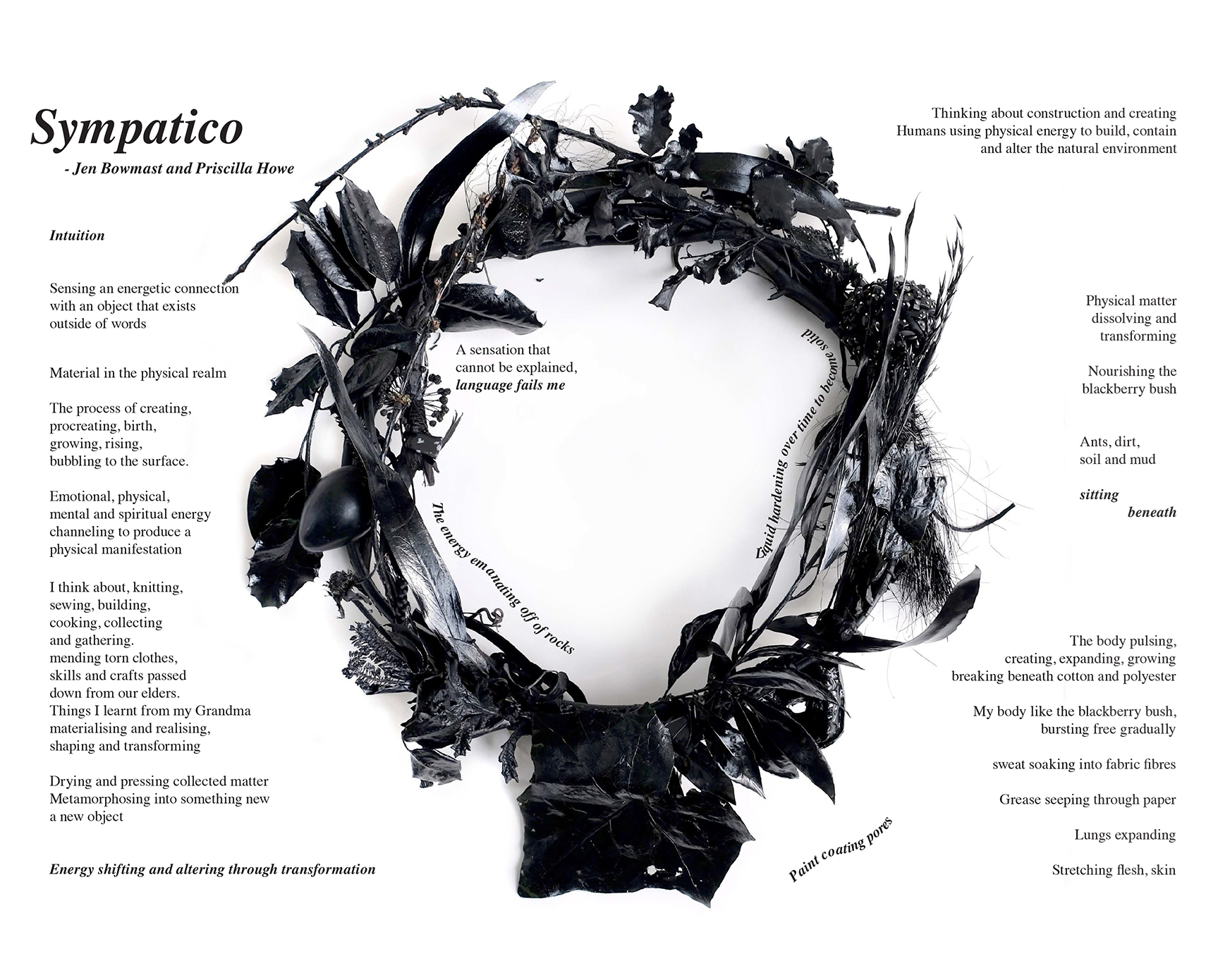

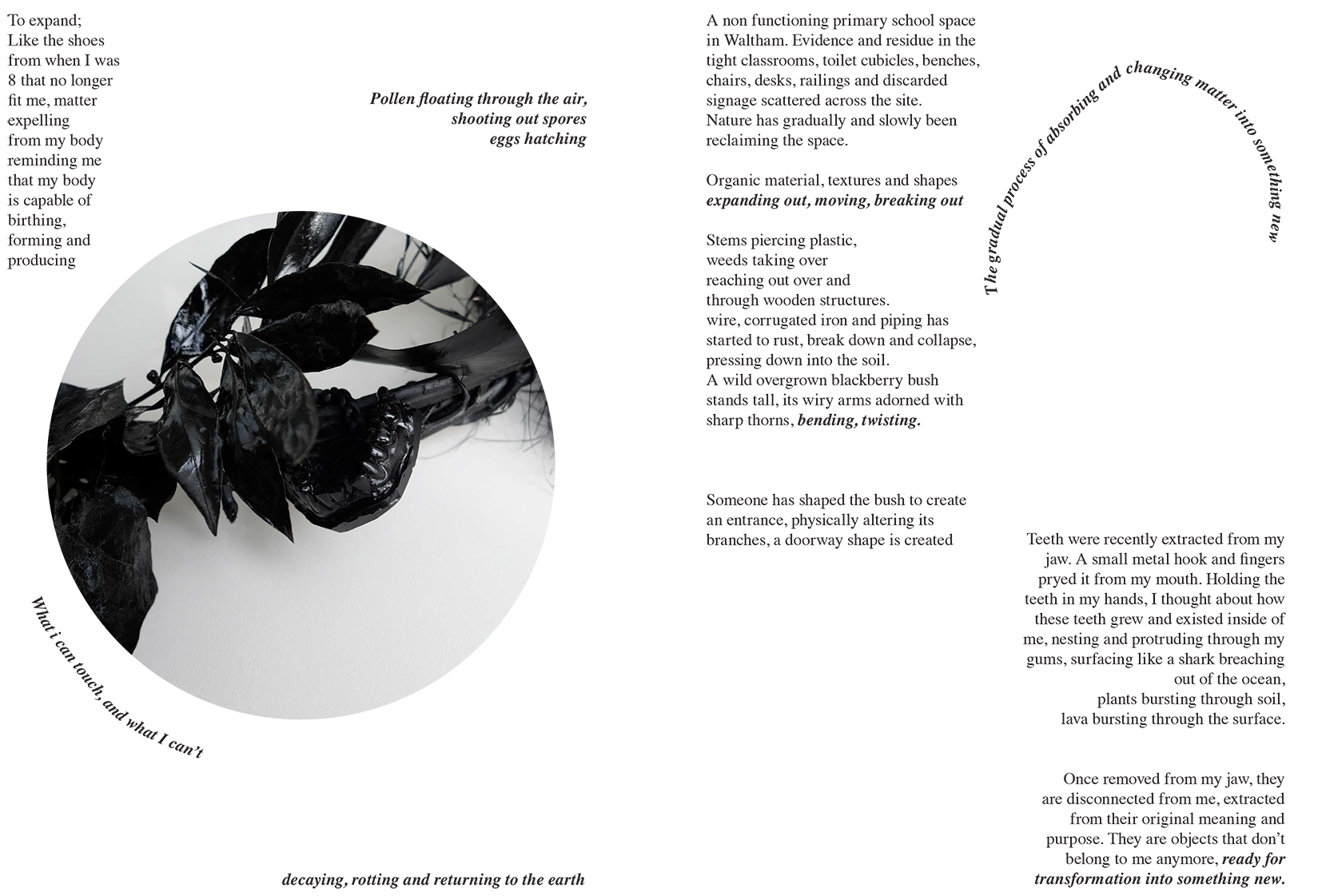

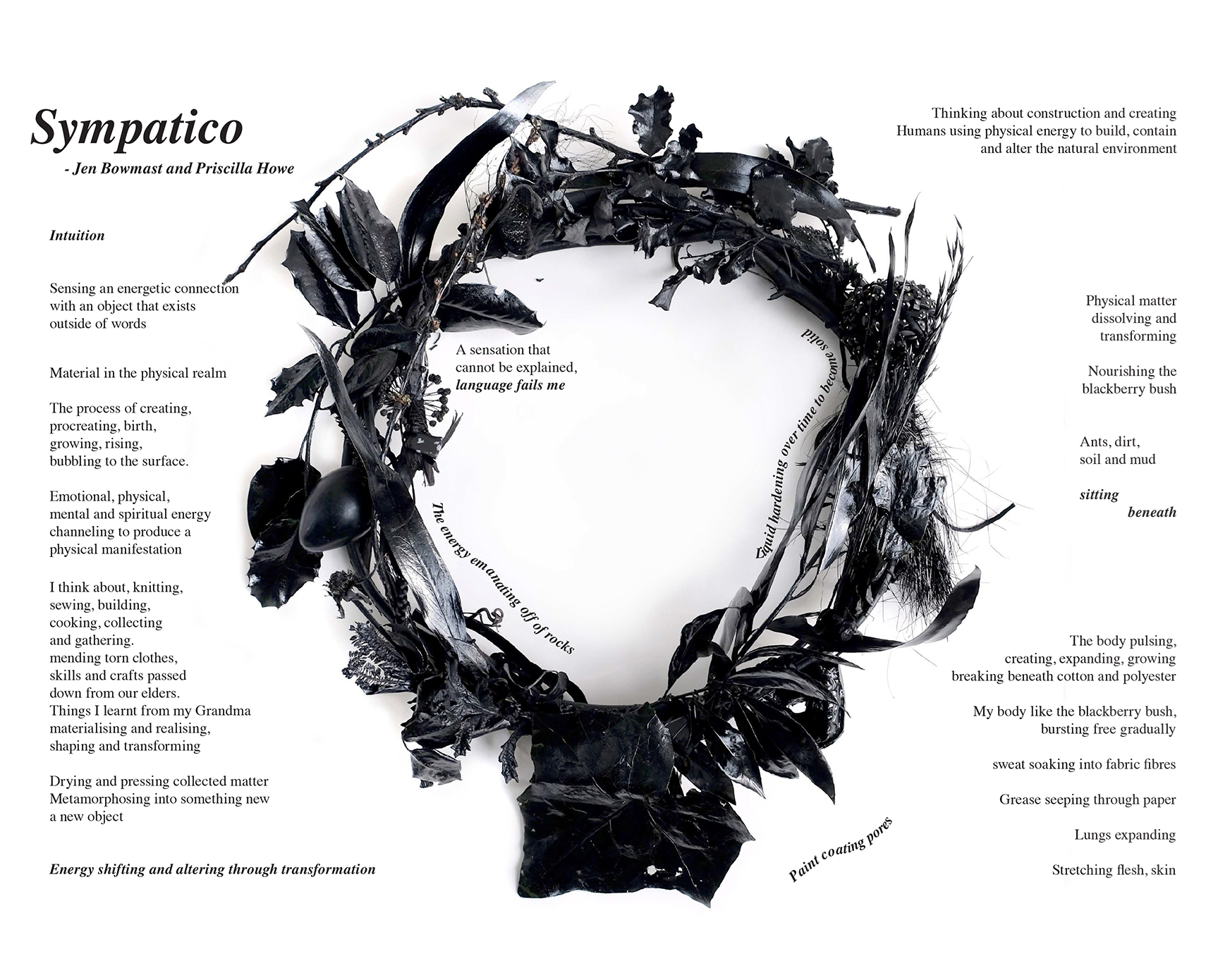

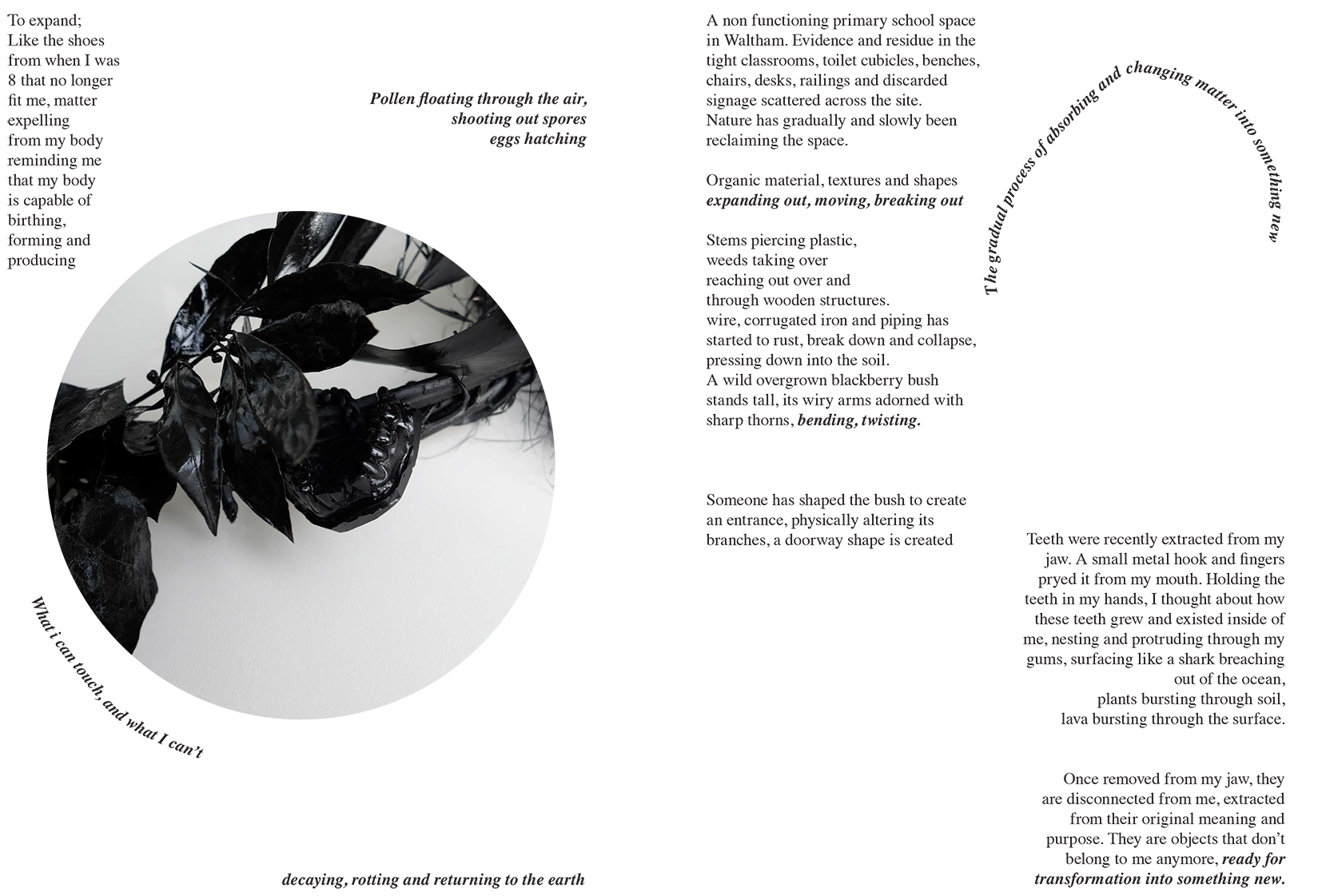

Jen Bowmast is a studio artist living in Ōtautahi Christchurch, creating installations to explore themes around spirituality. Jen considers the idea that art, both the making and experiencing, is a way to connect with other realms of experience, to interpret an inner vision, or as a mode of knowledge in itself. Within her art practice, encounters with clairvoyants are catalysts for haptic intuitive making with raw materials such as bronze, clay and stone. These artefacts are offered as transitional objects betwixt one place and another, reflecting the moment of exchange between artist and reader during esoteric meetings. Jen is interested in the position of the artist as querent, researching real and imagined relationships between artist, objects, materials and the space they inhabit. www.jenbowmast.com

Stella Corkery’s art practice traces emergent connections, operating among the diverse realms of painting, music and the feminine. Stella tends to bypass preparatory devices such as drawing and creates the work with some immediacy directly onto the canvas, improvising and problem solving in situ. References within her work can stretch across art history, contemporary art, popular culture and musical influences – for example post-punk and free jazz. The result is work that often appears to be traversing the non-linear yet still operates within conceptually unified systems. Stella also works outside of visual media, playing experimental music as a solo project and as part of the duo White Saucer.

Recent exhibitions include Paradises, Michael Lett, 2020 (solo); A Short Run: A Selection of New Zealand Lathe-Cut Records, The Dowse Art Museum, Lower Hutt, 2020 (group); Year of the Head, Olga Gallery, Ōtepoti, 2020 (solo); I’ve Seen Sunny Days, Goya Curtain, Tokyo, 2018 (solo); Theme for a Science Fiction Vampire, Michael Lett, 2017 (solo); Necessary Distraction: A Painting Show, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2015, (solo). Stella is represented by Michael Lett, Auckland, and lives and works in Auckland, New Zealand.

Lisa Crowley works in photography and moving image, and her practice draws on diverse lineages of feminist practice. These different strands of thought, spanning the scientific, the mystic and the creative, share an understanding of the natural world through embodied and speculative orientations.

Working with the traces of these practices, and by embedding them in the immanent and granular materiality of the analogue, Lisa proposes a different a logic for being. Her works reveal various forms of feminist ‘doing,’ the visual signs of which are dispersed amongst imagery of the animal and the mineral at work. In pairing the traces of the labour of embodied knowledge-making with the materiality of the world-in-process, Lisa’s work proposes a different kind of intelligence – one that speaks to affective and distributive forms of being. She lives and works in Auckland.

Andrea Gardner was born in California and completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at the University of California at Santa Cruz and a Master of Fine Arts in Painting from the University of Iowa. She has lived in numerous places including Montana, New York City, Rome, Italy and since 1995 has lived in Whanganui, New Zealand. She works primarily in photography and mixed media sculpture. She has work in the collections of The Dowse Art Museum, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, the Sarjeant Gallery and the James Wallace Trust.

www.andreagardner.co.nz

Gill Gatfield is a sculptor and author with a background in human rights and law reform. Across a wide range of media – physical, extended reality and text, she explores political and philosophical issues, and offers sensory encounters that can shift attitudes and ideas. Gill’s artworks transform unusual and unique materials into emotive abstract forms. Her work is exhibited and held in collections in New Zealand, Australia, North America and Europe.

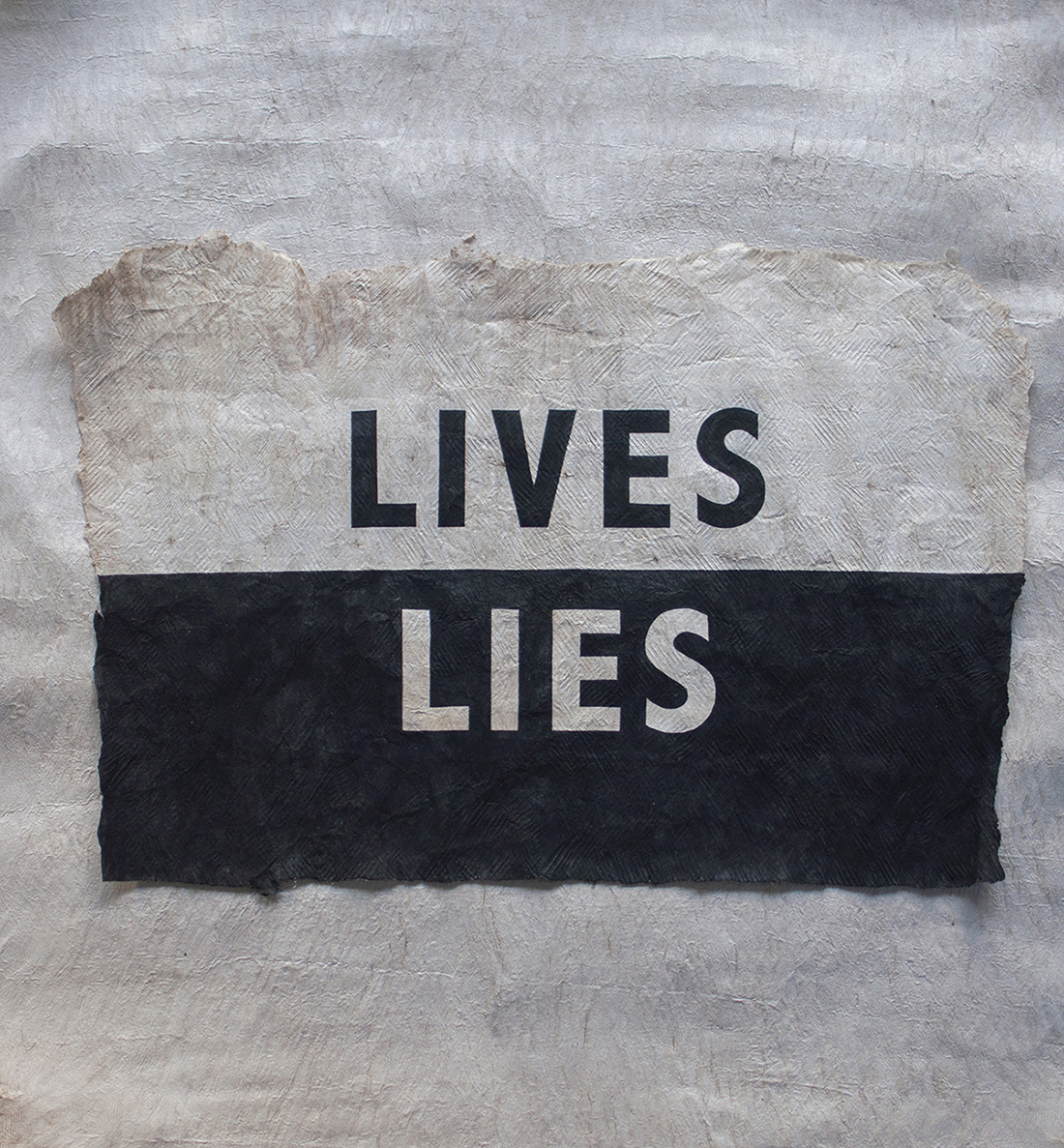

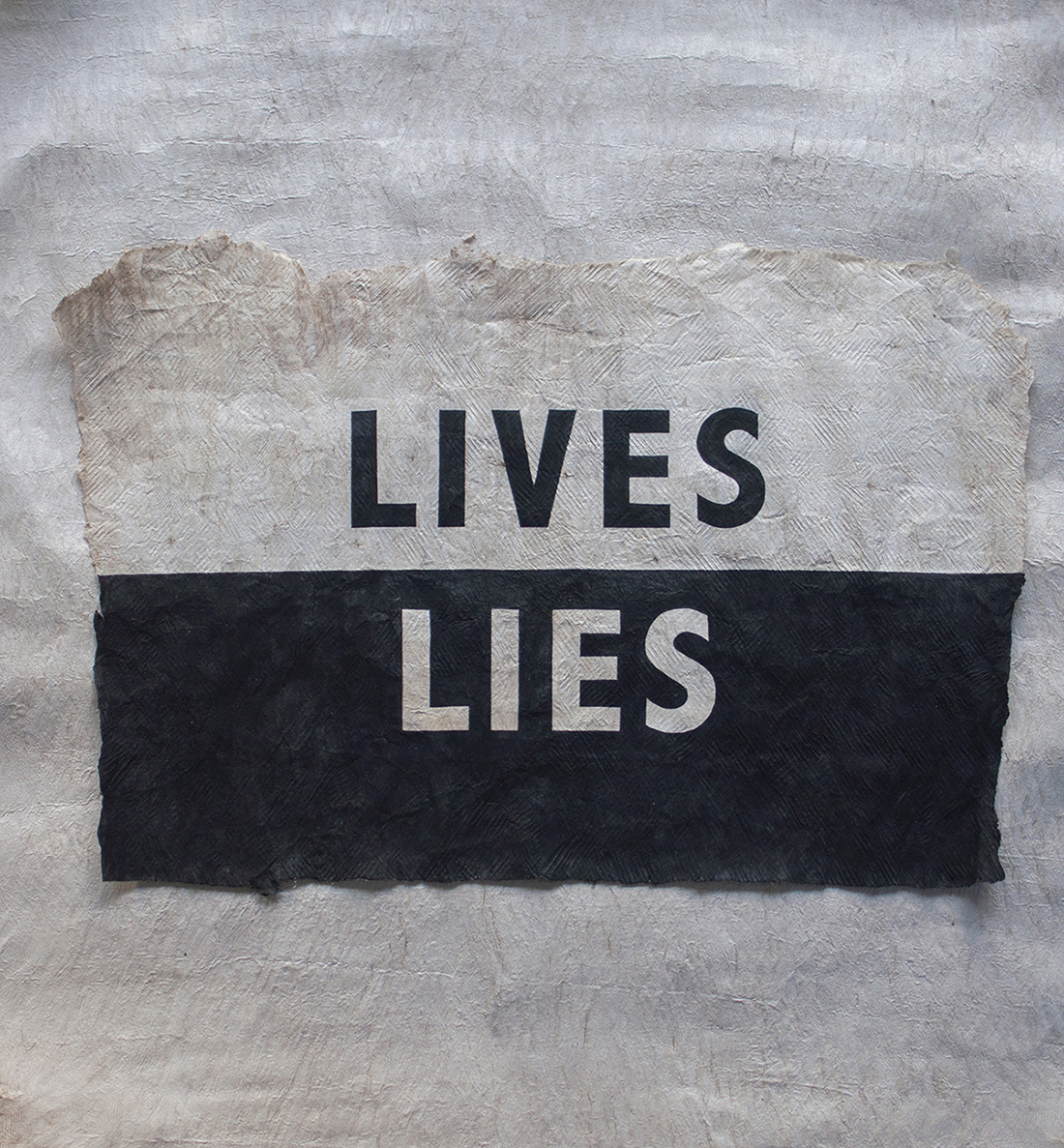

Nikau Hindin (Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi) is a multi-disciplinary artist with a revivalist agenda to re-awaken and remember the process of making aute (Māori tapa cloth). Her mission to re-learn this practice was influenced by the revitalisation of voyaging, navigation and her involvement with waka haurua throughout Te Moana-Nui-a-Kiwa.

This new wave of knowledge is recorded in Nikau’s new works. She articulates the mathematical precision of celestial navigation and uses the star compass to inform the marks created on her aute. She creates star maps in which every line denotes a star’s exact rising position on the horizon. These maps are spatial and temporal, to help her remember the declination of stars, as well as the way the night sky changes through the seasons.

Nikau created this piece in support of the Black Lives Matter Movement in the USA, and donated proceeds to the movement. Inherent in being a Moana person is the knowing that we are all connected, and oppression and racism affects us all.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Martin Luther King Jr.

Priscilla Howe is an artist, designer and writer from Ōtautahi Christchurch. Her practice is concerned with phenomenology, queerness, the supernatural and theatricality in the everyday. This enquiry spreads itself across her different media, predominantly using drawing to reimagine spaces, creating worlds that embrace female sexuality, queerness, supernatural forces and sex work. She views her design and writing practice as similar spaces to explore and embrace the unknown through intuition and playfulness.

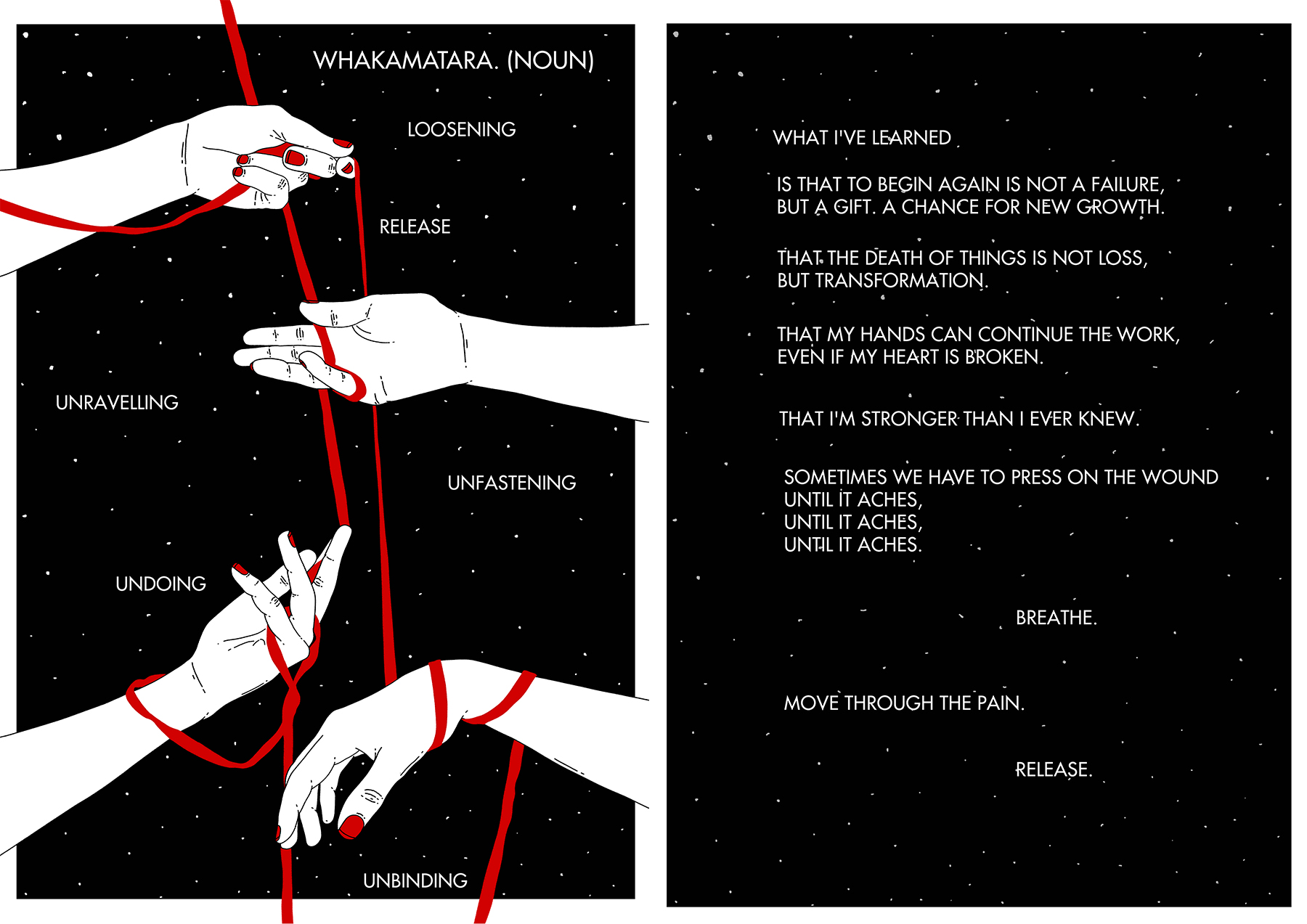

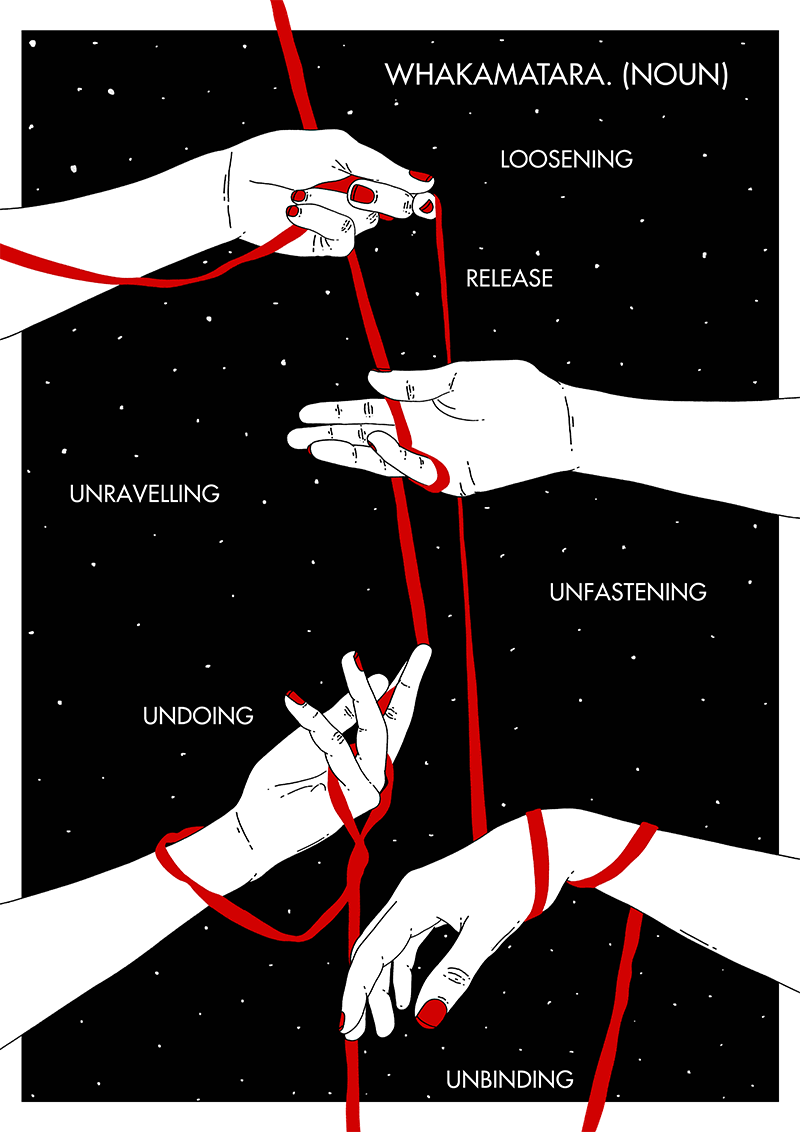

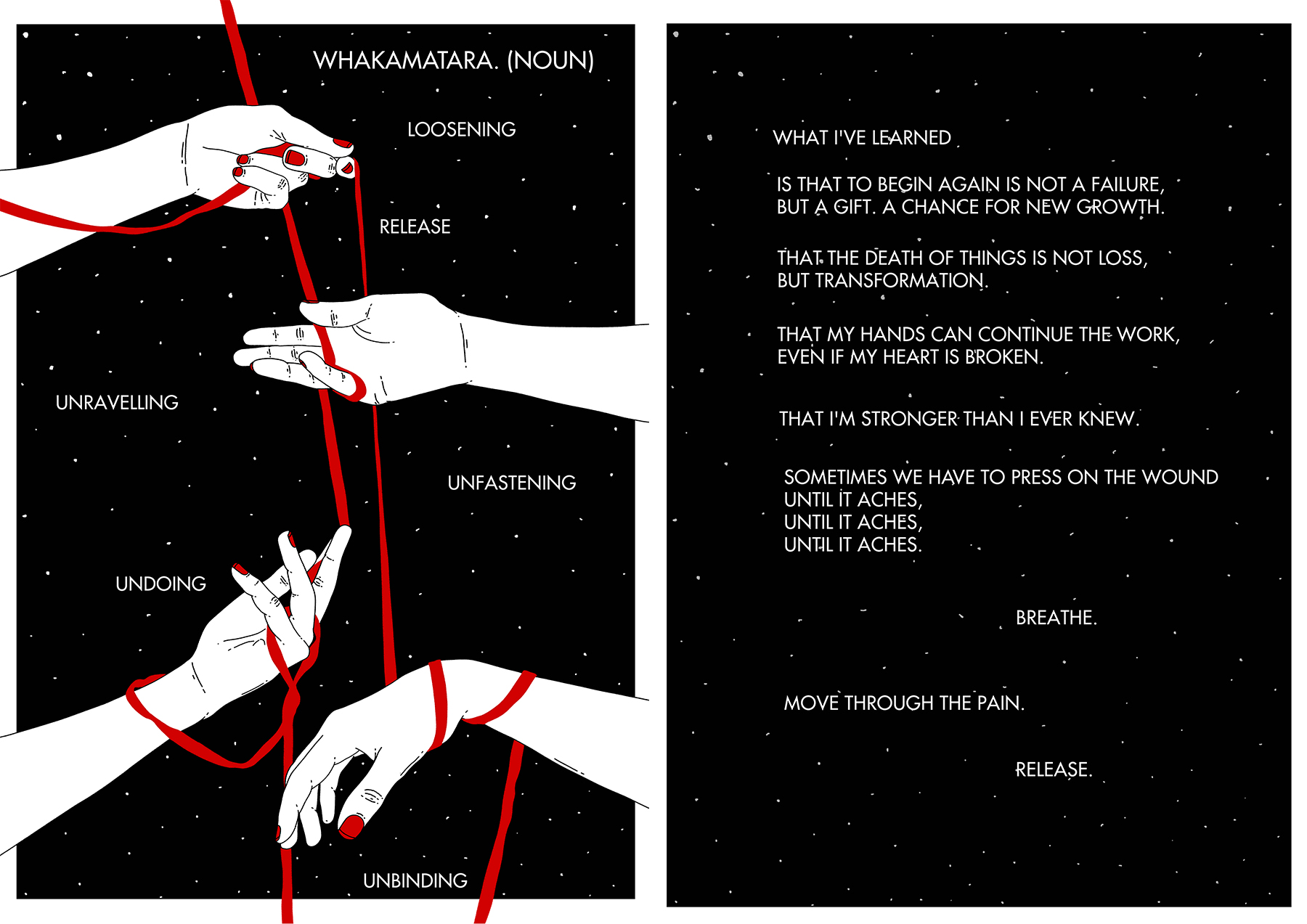

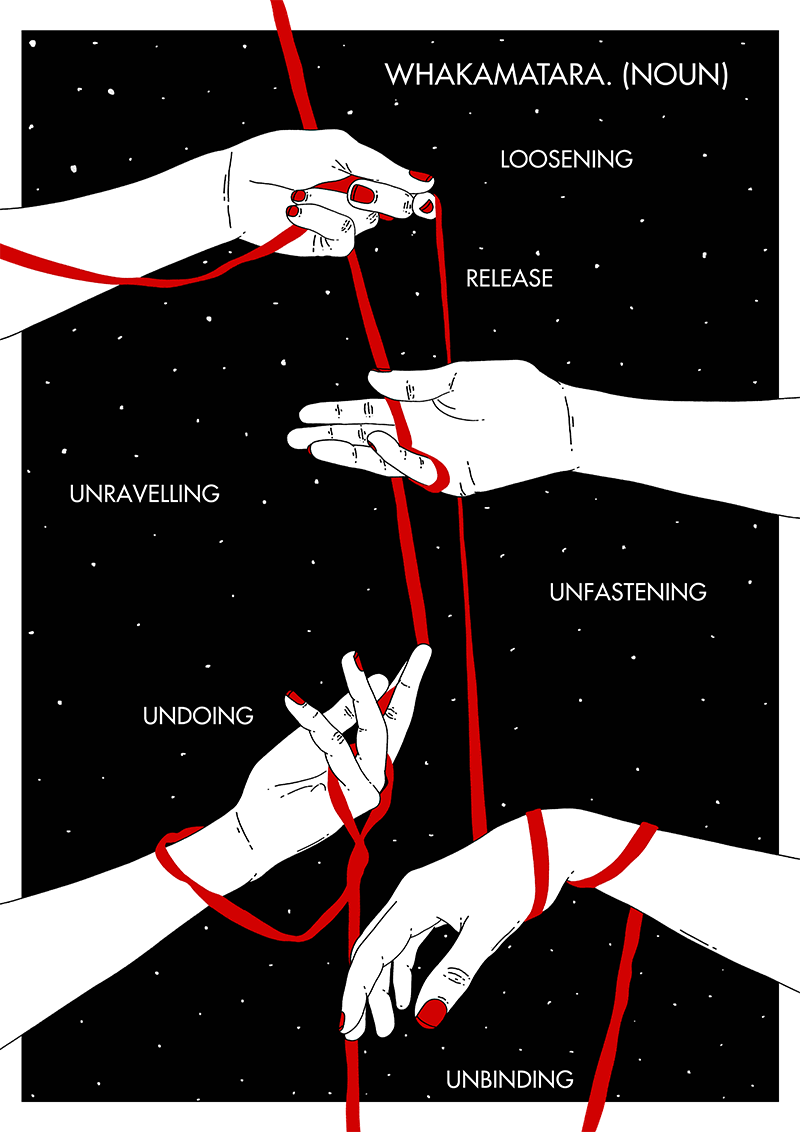

Vicktoria Johnson is a designer of Niuean and Māori heritage, living in Papakura, South Auckland. She completed a BFA in graphic design at Whitecliffe in 2018 and is now studying in the MFA programme at Whitecliffe. Her project is around language and is conceptually driven. She is currently working for RNZAF.

Yukari Kaihori is a visual artist of Japanese heritage, currently based in Tāmaki Makaurau. She is primarily a painter; her style and methods change from project to project but she often works around the theme of cultural, temporal and physical ‘in-between-ness’: being between Western and Eastern cultural values and between the permanent and the temporary physical properties of artwork. She is currently interested in the ‘here and now’ of present time, with a Shinto and Zen Buddhist point of view. She has exhibited her work in both public and private spaces including Places, ‘in-between’, Public Record, 2020; we painted the wall with cracks, play_station, 2020; This Land is All We Know, Hastings City Art Gallery, 2019.

She began training in Japanese calligraphy at the age of five and received her license at seventeen. Her interest in nature and mountains in the South Island brought her to New Zealand in 2009.

Claudia Kogachi is a Japanese-born (Awaji-Shima) artist working in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. She graduated from Elam School of Fine Arts, The University of Auckland, in 2018 with a Bachelor of Fine Arts with First Class Honours. Claudia was the recipient of the 2019 New Zealand Painting and Printmaking award for her painting Mom Wait Up (2019). Her most recent exhibitions include Uncle Gagi, Play Station, 2020, and The New Artist Show, Artspace Aotearoa, 2020.

Huriana Kopeke-Te Aho (Tūhoe, Ngāti Porou, Rongowhakaata, Te Āti Haunui-a-Pāpārangi, Ngāti Kahungunu, Fale‘ula) is a self-taught artist and illustrator whose work is primarily influenced by their Māori whakapapa, takatāpui identity and political beliefs. They have produced work for Waikato University, Tuatara Collective, Action Station, Auckland Pride, Organise Aotearoa, SOUL, Rainbow Youth and The Pantograph Punch, among others. Their illustrations have also been featured in Te Papa’s film series He Paki Taonga i a Māui and Protest Tautohetohe, published by Te Papa Press in 2019.

Cathy Livermore’s (Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe, Kāi Tahu, Pākehā) practices are currently focused in intercultural spaces of collaboration and in new media technologies, weaving together her passions for performance, te ao Māori, healing traditions and education. As an artist, educator, activist and healer Cathy has enjoyed the past 20 years performing, choreographing and teaching (as Head of Dance at Whitireia and then as Head of Dance at the Pacific Institute of Performing Arts) around the Southern and Northern Hemispheres, beginning in Australia and now residing in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Teresa Peters is an artist and filmmaker, currently working in clay and ceramics. She is interested in bodies, earth bodies, forming and transforming. She recently showed at Auckland Art Fair 2021 with the Mothermother Archive and RM Gallery and launched DISASTROUSFORMS.COM, made with the support of Creative New Zealand. Inspired by a field trip to Pompeii with Mark Dion in 2014 and Auckland Museum Collections Online, where it is now archived as a Topic, and screened on the Auckland Live Digital Stage, Aotea Square. After five years in Berlin and New York, she completed a PGDipFA at Elam, 2015 and was the Ceramics Creative Studio Resident at Studio One Toi Tu 2018/2019. Exhibitions include: ECHO BONE 2019 at Mothermother Archive alongside Judy Darragh and Natalie Tozer, Clay Dreams - Uku Moemoea, at Nathan Homestead and New Ceramics Acquisitions, the Pah Homestead, in March 2020, alongside Peter Hawkesby. Who Is Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf, at Te Tuhi, 2007, and at P.P.O.W Gallery, NYC, 2010. She will show at RM Gallery July 2021 in a group show of women artists exploring environmental agency. @disastrousforms

Elisabeth Pointon, who lives in Te Whanganui-a-Tara, is dedicated to interrogating the status quo, placing a particular emphasis on systemic failures relating to marginalised communities. Her work typically centres on text, and is marked by wit and slipperiness of meaning. The artist adapts language and display methods associated with sales and showrooms (she has long worked for a luxury car dealership), finding richness within expressions and forms that might otherwise seem generic or vacuous.

Ali Senescall is an Auckland-based artist. They graduated from Elam, University of Auckland, with a BFA in 2018. Ali’s practice is multidisciplinary but has recently been predominantly video based. Earlier this year they had a show at Parasite gallery titled As Above So Below. This show intends to read as a life review; the moment before you die your life flashes before you in the attempt to save yourself from death. Except instead of real life, these flashes were captured from movies that were very formative, such as Scarlet Diva (2000) and Ginger Snaps (2000). Ali also had a short film and a photograph in the most recent May Fair. The photograph was titled 2021 and showed a woman holding a bootleg Dior saddle that the artist had made. Ali’s video works and short films can be found on YouTube and they have a movie review Instagram account under the handle @d3vilsr3j3cts.

Rachel Shearer (Pākehā, Rongowhakaata, Te Aitanga ā Māhaki) explores sound through a range of practices – recording and performing experimental music, site-specific installation, audio-visual projects, research, writing, education and collaborations with practitioners of moving image and performance. She has been active as a recording and performing experimental musician and sound artist in Aotearoa and internationally for over 35 years.

Sriwhana Spong is an artist from Aotearoa New Zealand, of both Pākehā and Indonesian descent, living in London. She works across various media, including sculpture, film, performance and sound, and underlines the complexity of subjectivity by creating relations between disparate ideas and influences. In her works, experiential knowledge, autobiography and fiction are entangled with carefully researched materials and forms that reflect their particular cultural contexts and sources. Here Sriwhana also draws on the writings of female medieval mystics, attempting to translate their ‘mystic style’ into works that explore the relationship of the body to language, how it is written, and how it exceeds and escapes this inscribing.

Sriwhana studied at Elam School of Fine Arts, The University of Auckland, and completed an MFA at the Piet Zwart Institute, Rotterdam. Recent exhibitions include Honestly Speaking, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2020; castle-crystal, Edinburgh Arts Festival, Ida-Ida, Spike Island, Bristol, 2019; A hook but no fish, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth and Pump House Gallery, London, 2018; having-seen-snake, Michael Lett, Auckland, 2017; and Oceanic Feeling with Maria Taniguchi, ICA, Singapore, 2016.

Salome Tanuvasa is a multi-disciplinary artist based in Auckland, New Zealand. Using moving image, drawing, photography and sculpture, her work explores themes related to her immediate surroundings and her family life. Her Instagram account is @salometanuvasa.

Natalie Tozer is interested in the soft unfurling emergence of the next generation, in an overarching context of care, consideration, gift and long thinking. To explore and realise these interests, and as a response to Femisphere, Natalie founded the mothermother project, a permanent exhibition platform with female programming as its heart and kaupapa. This is a project that evolves as artists invite artists to explore a philosophy of exchange. The project fosters connections by providing space for artists to make contact with artists they admire, or whom they wish to thank or reach out to, or to simply acknowledge, to initiate an exchange of space. The taonga gifted to the project is the artist’s invitation to the next artist. This generational process aims to activate curatorial practice, challenging normative modes of gallery representation.

Nat’s personal practice also embodies this line of enquiry. In these modes of non-hierarchical, collective, circular thinking she is looking at symbiotic relationships, assemblages, entanglements, and improbable cohabitations and collaborations. Through surveying the ground and walking, her work explores the way we can amalgamate or fuse with our environments to access alternative futures.

Cora-Allan Wickliffe is a multi-disciplinary artist and curator of Māori and Niuean descent. A contemporary practitioner of the Niuean tradition of barkcloth known as hiapo, she is credited with reviving the ‘sleeping artform,’ which has not been practised in Niue for several generations. Her work is very important to the Niuean community and has been exhibited in Australia, Aotearoa, England and Niue. She has already had a sell-out exhibition in New Zealand and her work is in the collections of Te Papa and Auckland Museum. Cora-Allan has a Master of Visual Art and Design from AUT.

Alexa Wilson is a choreographer, performance artist, video artist and writer who has been based in Berlin for the last ten years, and is now back in Aotearoa. She has presented performance and video works across Aotearoa, Europe, Asia, North America and Australia. Her works have been performed in theatre and visual arts contexts including 21 Movements, Manifesta Biennial, 2017; Oracle, Sophiensaele Berlin, Artspace Auckland and The Physics Room, Christchurch; Breathless, Dixon Place, New York City; Peripheral Visions, Meinblau Gallery, Kule, and Ackerstadt Palast Month of Performance Art-Berlin, all 2015; 999, Morni Hills Biennale, India; Ugly Duck Gallery, London and Performance Art Week Aotearoa, Wellington. She has created full-length works for Footnote New Zealand Dance: The Status of Being, 2014, and The Dark Light, 2017. She has won four Auckland Fringe Awards for Weg: A-Way, 2011, and the Tup Lang Award for Toxic White Elephant Shock, 2009. She has curated Morni Hills Performance Residency in India, 2017, and is founder and artistic director of Experimental Dance Week Aotearoa 2019–20. She has a BA from The University of Auckland, a BPSA from Unitec, an MPhil from AUT and a PG Dip Fine Arts from Transart Institute Berlin/NYC. She is about to publish her first book, Theatre of Ocean.

Femisphere 4

Biographies

Alice Alva is a multi-disciplinary artist and art educator based in Te-Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, New Zealand, who works across drawing and illustration, embroidery and textiles, painting and graphic design. Her work is situated at the intersection between art and craft and the act of making. Alice has exhibited her work across Australia and New Zealand, including at the Wallace Gallery, Toi Pōneke, RM Gallery and Dunedin Public Art Gallery’s Rear Window Project. She was a finalist in the 27th Annual Wallace Art Award and the Parkin Drawing Prize 2018.

www.alicealva.com Instagram @glassandbones

Greta Anderson (b. Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand) completed a Master of Visual Arts Degree at Sydney College of the Arts in New South Wales (2006) and a Bachelor of Fine Arts at Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland (1999). Atmospheric and visually striking, Anderson’s draws cinematic qualities into her still photographic images, embuing them with mood and drama. Anderson often captures figures and objects in intermediary states, moving from day into night, stillness into potential. Her notable solo exhibition The Stand Ins was held at Te Tuhi, Pakuranga, Auckland (2003) and she has since been the recipient of several grants and awards. Anderson has been selected for numerous major exhibitions at important venues for contemporary art and photography including Gus Fisher Gallery (Auckland), the Australian Centre of Photography (Sydney), The University of Sydney, the Museum of Photographic Arts (San Diego), the Ringling Museum of Art (Sarasota) and the Archibald Prize at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (Sydney).

Anderson’s work has been featured in numerous photographic compendiums including Picturing Eden by Anthony Bannon and Deborah Klochko (2006), Future Images by Mario Cresci (2010), PhotoForum at 40: Counterculture, Clusters, and Debate in New Zealand by Nina Seja (2014), and See What I Can See: New Zealand Photography for the Young and Curious by Gregory O’Brien (2015). In addition, Anderson has a comprehensive commercial portfolio, having been invited to photograph campaigns for high-profile advertising agencies including Saatchi & Saatchi, DDB, and Mojo, and for editorials in the New Zealand Herald, Metro Magazine and the Australian Financial Review.

www.gretaanderson.com

Hana Pera Aoake (Ngaati Hinerangi, Ngaati Mahuta, Tainui/Waikato) is an artist and writer based in Waikouaiti on stolen Waitaha, Kaai Tahu and Kaati Mamoe whenua.

Grace Bader is a practising artist based in Auckland, New Zealand. Observing relationships between line and shape, her work plays with abstraction and the human figure. The idea of connection is central to her practice. She says, “I paint because I have to; it makes me feel. To feel is to be alive.” Grace is represented by Melanie Roger Gallery.

www.melanierogergallery.com www.gracebader.com Instagram @grace.bader

Gemma Banks is an Ōtautahi-born artist, designer and arts administrator. She graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts (First Class Honours) in Graphic Design. During her study she interned at Ilam Press, designing and printing artist’s books. From there she worked in-house at the Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. She has been involved in designing and Risograph printing a number of award-winning poetry books for Canterbury University Press and has recently been published in Share/Cheat/Unite and Hamster. She was nominated as a finalist in the AGDA Awards 2019 and the DINZ Best Awards 2019 for her work on Heart of Glass for Enjoy Contemporary Art Space.

Jen Bowmast is a studio artist living in Ōtautahi Christchurch, creating installations to explore themes around spirituality. Jen considers the idea that art, both the making and experiencing, is a way to connect with other realms of experience, to interpret an inner vision, or as a mode of knowledge in itself. Within her art practice, encounters with clairvoyants are catalysts for haptic intuitive making with raw materials such as bronze, clay and stone. These artefacts are offered as transitional objects betwixt one place and another, reflecting the moment of exchange between artist and reader during esoteric meetings. Jen is interested in the position of the artist as querent, researching real and imagined relationships between artist, objects, materials and the space they inhabit. www.jenbowmast.com

Stella Corkery’s art practice traces emergent connections, operating among the diverse realms of painting, music and the feminine. Stella tends to bypass preparatory devices such as drawing and creates the work with some immediacy directly onto the canvas, improvising and problem solving in situ. References within her work can stretch across art history, contemporary art, popular culture and musical influences – for example post-punk and free jazz. The result is work that often appears to be traversing the non-linear yet still operates within conceptually unified systems. Stella also works outside of visual media, playing experimental music as a solo project and as part of the duo White Saucer.

Recent exhibitions include Paradises, Michael Lett, 2020 (solo); A Short Run: A Selection of New Zealand Lathe-Cut Records, The Dowse Art Museum, Lower Hutt, 2020 (group); Year of the Head, Olga Gallery, Ōtepoti, 2020 (solo); I’ve Seen Sunny Days, Goya Curtain, Tokyo, 2018 (solo); Theme for a Science Fiction Vampire, Michael Lett, 2017 (solo); Necessary Distraction: A Painting Show, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2015, (solo). Stella is represented by Michael Lett, Auckland, and lives and works in Auckland, New Zealand.

Lisa Crowley works in photography and moving image, and her practice draws on diverse lineages of feminist practice. These different strands of thought, spanning the scientific, the mystic and the creative, share an understanding of the natural world through embodied and speculative orientations.

Working with the traces of these practices, and by embedding them in the immanent and granular materiality of the analogue, Lisa proposes a different a logic for being. Her works reveal various forms of feminist ‘doing,’ the visual signs of which are dispersed amongst imagery of the animal and the mineral at work. In pairing the traces of the labour of embodied knowledge-making with the materiality of the world-in-process, Lisa’s work proposes a different kind of intelligence – one that speaks to affective and distributive forms of being. She lives and works in Auckland.

Andrea Gardner was born in California and completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at the University of California at Santa Cruz and a Master of Fine Arts in Painting from the University of Iowa. She has lived in numerous places including Montana, New York City, Rome, Italy and since 1995 has lived in Whanganui, New Zealand. She works primarily in photography and mixed media sculpture. She has work in the collections of The Dowse Art Museum, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, the Sarjeant Gallery and the James Wallace Trust.

www.andreagardner.co.nz

Gill Gatfield is a sculptor and author with a background in human rights and law reform. Across a wide range of media – physical, extended reality and text, she explores political and philosophical issues, and offers sensory encounters that can shift attitudes and ideas. Gill’s artworks transform unusual and unique materials into emotive abstract forms. Her work is exhibited and held in collections in New Zealand, Australia, North America and Europe.

Nikau Hindin (Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi) is a multi-disciplinary artist with a revivalist agenda to re-awaken and remember the process of making aute (Māori tapa cloth). Her mission to re-learn this practice was influenced by the revitalisation of voyaging, navigation and her involvement with waka haurua throughout Te Moana-Nui-a-Kiwa.

This new wave of knowledge is recorded in Nikau’s new works. She articulates the mathematical precision of celestial navigation and uses the star compass to inform the marks created on her aute. She creates star maps in which every line denotes a star’s exact rising position on the horizon. These maps are spatial and temporal, to help her remember the declination of stars, as well as the way the night sky changes through the seasons.

Nikau created this piece in support of the Black Lives Matter Movement in the USA, and donated proceeds to the movement. Inherent in being a Moana person is the knowing that we are all connected, and oppression and racism affects us all.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Martin Luther King Jr.

Priscilla Howe is an artist, designer and writer from Ōtautahi Christchurch. Her practice is concerned with phenomenology, queerness, the supernatural and theatricality in the everyday. This enquiry spreads itself across her different media, predominantly using drawing to reimagine spaces, creating worlds that embrace female sexuality, queerness, supernatural forces and sex work. She views her design and writing practice as similar spaces to explore and embrace the unknown through intuition and playfulness.

Vicktoria Johnson is a designer of Niuean and Māori heritage, living in Papakura, South Auckland. She completed a BFA in graphic design at Whitecliffe in 2018 and is now studying in the MFA programme at Whitecliffe. Her project is around language and is conceptually driven. She is currently working for RNZAF.

Yukari Kaihori is a visual artist of Japanese heritage, currently based in Tāmaki Makaurau. She is primarily a painter; her style and methods change from project to project but she often works around the theme of cultural, temporal and physical ‘in-between-ness’: being between Western and Eastern cultural values and between the permanent and the temporary physical properties of artwork. She is currently interested in the ‘here and now’ of present time, with a Shinto and Zen Buddhist point of view. She has exhibited her work in both public and private spaces including Places, ‘in-between’, Public Record, 2020; we painted the wall with cracks, play_station, 2020; This Land is All We Know, Hastings City Art Gallery, 2019.

She began training in Japanese calligraphy at the age of five and received her license at seventeen. Her interest in nature and mountains in the South Island brought her to New Zealand in 2009.

Claudia Kogachi is a Japanese-born (Awaji-Shima) artist working in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. She graduated from Elam School of Fine Arts, The University of Auckland, in 2018 with a Bachelor of Fine Arts with First Class Honours. Claudia was the recipient of the 2019 New Zealand Painting and Printmaking award for her painting Mom Wait Up (2019). Her most recent exhibitions include Uncle Gagi, Play Station, 2020, and The New Artist Show, Artspace Aotearoa, 2020.

Huriana Kopeke-Te Aho (Tūhoe, Ngāti Porou, Rongowhakaata, Te Āti Haunui-a-Pāpārangi, Ngāti Kahungunu, Fale‘ula) is a self-taught artist and illustrator whose work is primarily influenced by their Māori whakapapa, takatāpui identity and political beliefs. They have produced work for Waikato University, Tuatara Collective, Action Station, Auckland Pride, Organise Aotearoa, SOUL, Rainbow Youth and The Pantograph Punch, among others. Their illustrations have also been featured in Te Papa’s film series He Paki Taonga i a Māui and Protest Tautohetohe, published by Te Papa Press in 2019.

Cathy Livermore’s (Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe, Kāi Tahu, Pākehā) practices are currently focused in intercultural spaces of collaboration and in new media technologies, weaving together her passions for performance, te ao Māori, healing traditions and education. As an artist, educator, activist and healer Cathy has enjoyed the past 20 years performing, choreographing and teaching (as Head of Dance at Whitireia and then as Head of Dance at the Pacific Institute of Performing Arts) around the Southern and Northern Hemispheres, beginning in Australia and now residing in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Teresa Peters is an artist and filmmaker, currently working in clay and ceramics. She is interested in bodies, earth bodies, forming and transforming. She recently showed at Auckland Art Fair 2021 with the Mothermother Archive and RM Gallery and launched DISASTROUSFORMS.COM, made with the support of Creative New Zealand. Inspired by a field trip to Pompeii with Mark Dion in 2014 and Auckland Museum Collections Online, where it is now archived as a Topic, and screened on the Auckland Live Digital Stage, Aotea Square. After five years in Berlin and New York, she completed a PGDipFA at Elam, 2015 and was the Ceramics Creative Studio Resident at Studio One Toi Tu 2018/2019. Exhibitions include: ECHO BONE 2019 at Mothermother Archive alongside Judy Darragh and Natalie Tozer, Clay Dreams - Uku Moemoea, at Nathan Homestead and New Ceramics Acquisitions, the Pah Homestead, in March 2020, alongside Peter Hawkesby. Who Is Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf, at Te Tuhi, 2007, and at P.P.O.W Gallery, NYC, 2010. She will show at RM Gallery July 2021 in a group show of women artists exploring environmental agency. @disastrousforms

Elisabeth Pointon, who lives in Te Whanganui-a-Tara, is dedicated to interrogating the status quo, placing a particular emphasis on systemic failures relating to marginalised communities. Her work typically centres on text, and is marked by wit and slipperiness of meaning. The artist adapts language and display methods associated with sales and showrooms (she has long worked for a luxury car dealership), finding richness within expressions and forms that might otherwise seem generic or vacuous.

Ali Senescall is an Auckland-based artist. They graduated from Elam, University of Auckland, with a BFA in 2018. Ali’s practice is multidisciplinary but has recently been predominantly video based. Earlier this year they had a show at Parasite gallery titled As Above So Below. This show intends to read as a life review; the moment before you die your life flashes before you in the attempt to save yourself from death. Except instead of real life, these flashes were captured from movies that were very formative, such as Scarlet Diva (2000) and Ginger Snaps (2000). Ali also had a short film and a photograph in the most recent May Fair. The photograph was titled 2021 and showed a woman holding a bootleg Dior saddle that the artist had made. Ali’s video works and short films can be found on YouTube and they have a movie review Instagram account under the handle @d3vilsr3j3cts.

Rachel Shearer (Pākehā, Rongowhakaata, Te Aitanga ā Māhaki) explores sound through a range of practices – recording and performing experimental music, site-specific installation, audio-visual projects, research, writing, education and collaborations with practitioners of moving image and performance. She has been active as a recording and performing experimental musician and sound artist in Aotearoa and internationally for over 35 years.

Sriwhana Spong is an artist from Aotearoa New Zealand, of both Pākehā and Indonesian descent, living in London. She works across various media, including sculpture, film, performance and sound, and underlines the complexity of subjectivity by creating relations between disparate ideas and influences. In her works, experiential knowledge, autobiography and fiction are entangled with carefully researched materials and forms that reflect their particular cultural contexts and sources. Here Sriwhana also draws on the writings of female medieval mystics, attempting to translate their ‘mystic style’ into works that explore the relationship of the body to language, how it is written, and how it exceeds and escapes this inscribing.

Sriwhana studied at Elam School of Fine Arts, The University of Auckland, and completed an MFA at the Piet Zwart Institute, Rotterdam. Recent exhibitions include Honestly Speaking, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2020; castle-crystal, Edinburgh Arts Festival, Ida-Ida, Spike Island, Bristol, 2019; A hook but no fish, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth and Pump House Gallery, London, 2018; having-seen-snake, Michael Lett, Auckland, 2017; and Oceanic Feeling with Maria Taniguchi, ICA, Singapore, 2016.

Salome Tanuvasa is a multi-disciplinary artist based in Auckland, New Zealand. Using moving image, drawing, photography and sculpture, her work explores themes related to her immediate surroundings and her family life. Her Instagram account is @salometanuvasa.

Natalie Tozer is interested in the soft unfurling emergence of the next generation, in an overarching context of care, consideration, gift and long thinking. To explore and realise these interests, and as a response to Femisphere, Natalie founded the mothermother project, a permanent exhibition platform with female programming as its heart and kaupapa. This is a project that evolves as artists invite artists to explore a philosophy of exchange. The project fosters connections by providing space for artists to make contact with artists they admire, or whom they wish to thank or reach out to, or to simply acknowledge, to initiate an exchange of space. The taonga gifted to the project is the artist’s invitation to the next artist. This generational process aims to activate curatorial practice, challenging normative modes of gallery representation.

Nat’s personal practice also embodies this line of enquiry. In these modes of non-hierarchical, collective, circular thinking she is looking at symbiotic relationships, assemblages, entanglements, and improbable cohabitations and collaborations. Through surveying the ground and walking, her work explores the way we can amalgamate or fuse with our environments to access alternative futures.

Cora-Allan Wickliffe is a multi-disciplinary artist and curator of Māori and Niuean descent. A contemporary practitioner of the Niuean tradition of barkcloth known as hiapo, she is credited with reviving the ‘sleeping artform,’ which has not been practised in Niue for several generations. Her work is very important to the Niuean community and has been exhibited in Australia, Aotearoa, England and Niue. She has already had a sell-out exhibition in New Zealand and her work is in the collections of Te Papa and Auckland Museum. Cora-Allan has a Master of Visual Art and Design from AUT.

Alexa Wilson is a choreographer, performance artist, video artist and writer who has been based in Berlin for the last ten years, and is now back in Aotearoa. She has presented performance and video works across Aotearoa, Europe, Asia, North America and Australia. Her works have been performed in theatre and visual arts contexts including 21 Movements, Manifesta Biennial, 2017; Oracle, Sophiensaele Berlin, Artspace Auckland and The Physics Room, Christchurch; Breathless, Dixon Place, New York City; Peripheral Visions, Meinblau Gallery, Kule, and Ackerstadt Palast Month of Performance Art-Berlin, all 2015; 999, Morni Hills Biennale, India; Ugly Duck Gallery, London and Performance Art Week Aotearoa, Wellington. She has created full-length works for Footnote New Zealand Dance: The Status of Being, 2014, and The Dark Light, 2017. She has won four Auckland Fringe Awards for Weg: A-Way, 2011, and the Tup Lang Award for Toxic White Elephant Shock, 2009. She has curated Morni Hills Performance Residency in India, 2017, and is founder and artistic director of Experimental Dance Week Aotearoa 2019–20. She has a BA from The University of Auckland, a BPSA from Unitec, an MPhil from AUT and a PG Dip Fine Arts from Transart Institute Berlin/NYC. She is about to publish her first book, Theatre of Ocean.

Femisphere 4

Gill Gatfield

Inclusive Monuments

Under the crystallising lens of #BlackLivesMatter, the false histories and trauma embedded in our colonial monuments are unfolding. Shadows cast by statues of glorified ‘founding fathers’ stain the ground, unravelling a legacy of oppression, exploitation and violent conquest. Challenges and calls to review and replace these symbols need a plan of action, not only with regard to the promises of Te Tiriti o Waitangi but also under the gender spotlights of #TimesUp and #MeToo.

Women in Aotearoa have protested female exclusion from the public realm since colonisation began – from being denied the legal rights of ‘a person’ in the late nineteenth century, including the right to vote, to objecting to an overarching male symbolism in public space. In the context of a then new 1977 law promising equal rights for women, Māori and other marginalised groups, Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu, when opening the Waikato Savings Bank Building in Hamilton, pointed to the bank’s crest – “a Ram’s Head between two Bulls’ Heads,” and said:

May I suggest that it would be prudent –

in view of the Human Rights Commission Act …

if, on your shield at least one bull

were replaced by a cow.

Quotable New Zealand Women (Reed, 1994, np)

The Māori Queen’s quip made the connection between symbolism and human rights, and how these coexist in the public domain. Public cultural objects are powerful outward expressions of both the status of individuals and their values, and the state of equality in a nation or place.

Elevated notions of power and commercial value attach to masculine symbols, giving reason to a bank’s choice of rams and bulls. This translated into a University of Auckland Master of Fine Arts Painting Reader, a compilation of recommended texts – 90 percent penned by men, and almost exclusively about man-made art. On the cover, a tongue-in-cheek yet salient script from a John Baldessari painting Tips for Artists (1967-68):

Tips For Artists Who Want To Sell

…

Subject Matter is Important: It has been said that paintings with cows and hens in them collect dust … while the same paintings with bulls and roosters sell.

From paintings to sculptures, the bull reigns supreme – presiding over the pavements of Wall Street and mounted on countless pedestals. In a textbook mise en scène, Kristen Visbal’s Fearless Girl faced off with Arturo Di Modica’s Charging Bull in Manhattan for one year before being removed to stand alone, amidst complaints the Girl was a commercial ploy and faux feminism, detracting meaning and attention from the bull – itself a symbol of capitalism and full-frontal masculinity.

Across Aotearoa, a parade of colonial male muscle occupies pedestals and parks. Commemorated British-born politicians and leaders include those who orchestrated or led invasions of Māori pā and mana whenua, upheld the oppression of Māori and profited from stolen land. Among these ‘founding fathers’ are abusers and oppressors of women, and political leaders who repeatedly undermined women’s efforts to win the right to vote and used their power to deny New Zealand women the basic human rights.

In the nation’s capital alone, there are over 150 pieces of public art. Of the eighteen figurative statues, only two honour individual women – the colonial British monarch Queen Victoria and New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield. Only one Māori female figure stands in Pōneke Wellington, featured in the sculpture Hinerangi by Māori arts leader and artist Darcy Nicholas QSO, at Pukeahu National War Memorial Park. At a televised election debate between women party leaders in 2020, political promises were made to install one more monument in the Capital, honouring an otherwise absent nineteenth century Pākehā suffragist leader, Kate Sheppard.

Two memorials in Pōneke Wellington honour the British brothers William and Edward Gibbon Wakefield. They were imprisoned in England for abducting a 15-year-old girl from her school and forcing her into marriage for a ransom; a precursor to their exploits leading the New Zealand Company, a government-sanctioned enterprise that amassed and on-sold Māori land. In the Octagon at Ōtepoti Dunedin, a UNESCO City of Literature, a monument to Scottish bard Robbie Burns celebrates a sexual predator outed by poet Liz Lochhead in 2018 as Weinsteinian.

On the forecourt of Parliament, a larger-than-life Premier Richard Seddon, who actively obstructed women’s suffrage for years, stands centre stage. A 2020 #DitchDick campaign demands the statue’s removal, listing Seddon’s “opposition to women’s rights, promotion of racist policy against Chinese people, support for widespread confiscations and coercive purchase of Māori land, and attempts to invade and annex the Pacific nations of Fiji, Sāmoa and the Cook Islands, succeeding in the latter.” This is streets away from the narrative on the capital city’s official website asserting the Seddon statue “importantly injects a degree of humanity into the grounds, reinforcing the idea that Government is made of the people.”

As hidden histories emerge, how can we explain and elevate these figures’ contributions above their culpability for causing systemic and/or serious harm? If public art has power to engage human hearts, minds and spirits, then today those monuments serve only to reinforce and create further intergenerational harm. Caption rewriting cannot remedy or mitigate the cruel psychology of a glorified oppressor’s presence in public space. Such monuments belong in the Oppression Wing of an Aotearoa Museum for Women, with a shared boundary to the larger Museum of Racial Injustice – two containers for relics of a past for which there is no place in the present.

New monuments are needed of ancestors, activists and wāhine toa. The National Council of Women listed eight women worthy of a statue in the capital:

Meri Te Tai Mangakāhia – women's suffrage leader

Kate Sheppard – women's suffrage leader

Dame Whina Cooper – Māori women's activist

Princess Te Puea Herangi – Kīngitanga movement leader

Jean Batten – aviator and first person to fly solo from England to New Zealand

Kate Edger – first woman in New Zealand to gain a university degree

Whetu Tirikatene-Sullivan – long-serving MP

Elizabeth McCombs – first woman elected to parliament in New Zealand

There are many more.

A 2020 survey of 500 Māori generated a list of figures who inspired and created, including advocates, navigators, gardeners and tohunga. Tomorrow’s monuments might also honour the scientists, health-care workers, volunteers and essential services confronting Covid-19. Future monuments need not be limited to representing history and human aspiration in figure form. As Leonie Hayden (The Spinoff’s Ātea Editor) says, “What about monuments to generosity? To creation?” The project of democratising public space will allow and celebrate a refreshing diversity of expression and thought.

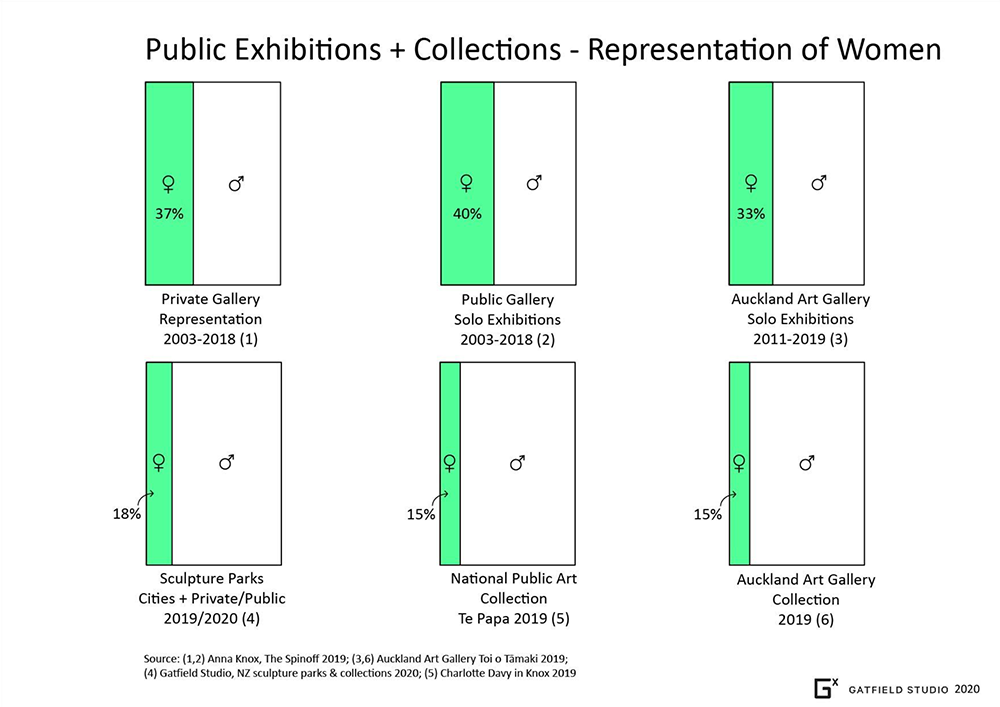

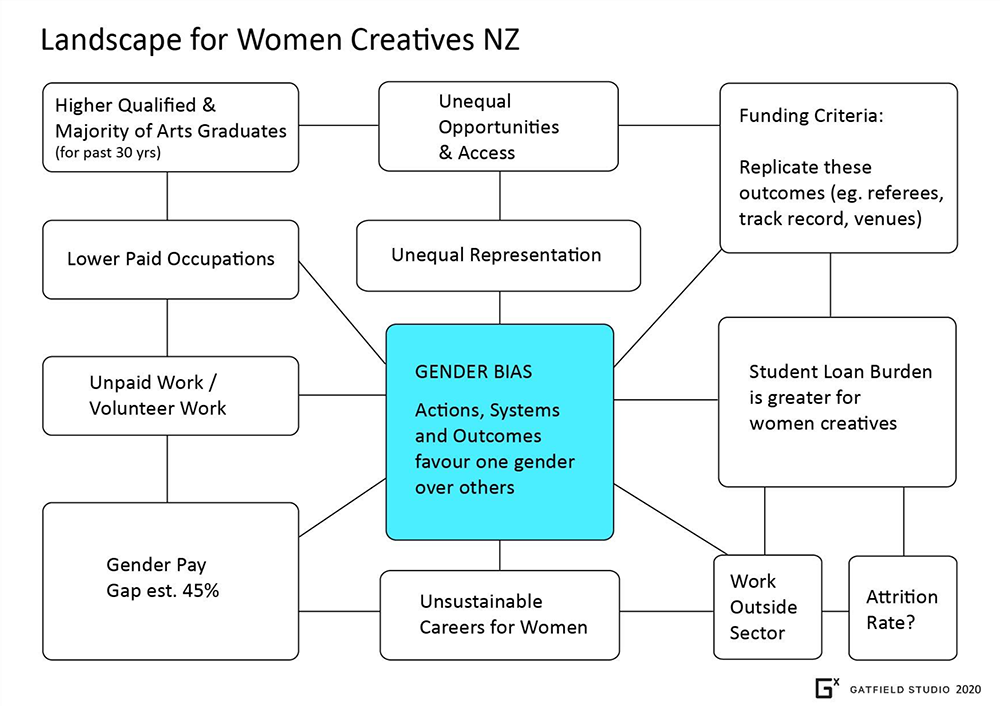

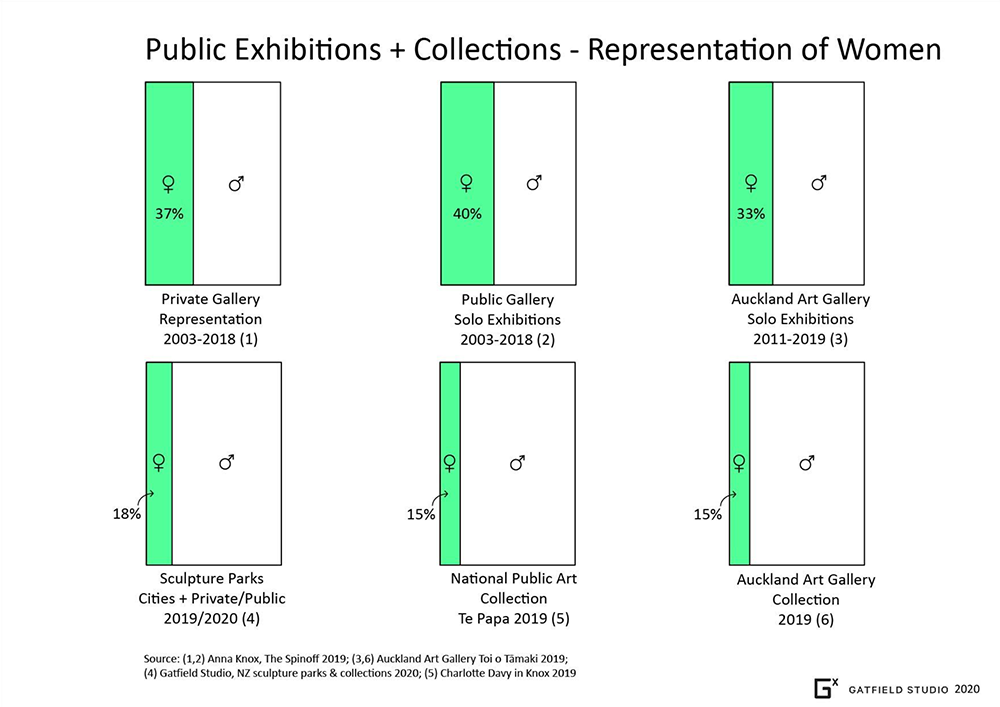

Attention also needs to be directed toward the commissioning process and the makers of public art. With rare exceptions (typically only when a woman is commissioned to make a statue or memorial for a woman), our public art makers are predominantly European and Pākehā men. The curated spaces of public sculpture exhibitions and sculpture parks reveal the particular function they play in creating the conditions that enable male artists to sustain a practice and to engage in public art.

At the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art Sculpture Park in Denmark, a permanent survey of international modern and contemporary work is listed among ‘The World’s Best Open-Air Museums.’ In 2015, I studied these works in what one commentator described as “all the modern masters of the art of sculpture,” and wrote in Art News New Zealand: “There’s no work by women artists in the Louisiana Sculpture Park, yet.” Five years later, there are still no women sculptors in this important collection.

In 2019, at the iconic Storm King, in upstate New York, one of the largest collections of outdoor sculpture in the world, I counted eighty-two artists in the permanent collection including long-term loans. Only fifteen of the artists were women – 18 percent. Beside Ursula von Rydingsvard’s Luba, in fading light, I staged a virtual Native Tongue, the alter ego of an ancient kauri sculpture: literally an Other I. The ephemeral companion momentarily nudged the proportion of women artists up closer to 20 percent. Numbers and pronouns are political. What’s measured, counts.

Gill Gatfield, Storm Queen, 2019.

(Native Tongue AR, 2018, with Ursula von Rydingsvard, Luba, 2009–10, at Storm King, New York)

Male occupation of public space is measured also through the pages of academia. Amazon recently delivered a much anticipated new book – Abstraction Matters: Contemporary Sculptors in Their Own Words (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019). The text expounds on the ideas of fourteen sculptors, including current practitioners, selected for being “not only eminent artists who made their mark in the contemporary sculptural landscape: they are also sharp and insightful theorists, inclined to reflect intensely upon the sense of their own work in particular and upon the nature of abstract sculpture in general.” The sculptors in Abstraction Matters are all men. The project demarcates a paradigm in which the makers’ heroic work and texts define the canon. There is literally no room for the Other. As a practitioner of abstraction, I sawed the book in half.

There’s no shortage of women contenders for sculpture books, parks and public collections. Smart public bodies like the UK Arts Council acquired 250 sculptures and installations by more than 150 women, across seventy-five years, including ‘ambitious work’ – the content for a major 2020 touring show in the UK, Breaking the Mould: Sculpture by Women Since 1945. In Los Angeles, Hauser Wirth & Schimmel’s exhibition Revolution in the Making: Abstract Sculpture by Women, 1947–2016 presented 100 works by thirty-four international women artists, tracing ways in which women have “changed the course of art by deftly transforming the language of sculpture since the post-war period.”

I think of Anni Albers, who was prevented from studying architecture at the Bauhaus, and directed instead to learn weaving, as “women were unsuited to the rigours of geometry.” Not content with her allocated art form being demoted to second rate, Albers disrupted that canon and built walls of fabric.

Gill Gatfield, Get Even – Abstraction Matters, 2020

Cities and sculpture exhibitions and parks in Aotearoa bulge with old and new artworks by male artists. Where doors are open, female artists demonstrate innovation, capacity and experience in making outdoor public work, and present challenging works in large numbers in successive national exhibitions such as the NZ Sculpture OnShore, a Women’s Refuge fundraiser, in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. Signs of a glass ceiling surface in the commissioning of permanent public work, and in the numbers of female artists shrinking as the prestige of a sculpture exhibition and the rewards on offer increase. At the ratepayer- and patron-funded biannual Auckland Botanic Gardens Sculpture in the Gardens 2015–2016, less than one quarter of artists selected were women (24 percent). Similarly in the biannual exhibition headland Sculpture on the Gulf 2017, women artists made up just over one quarter of those selected (27.5 percent).

These numbers are reflected in the gender-skewed picture of commissioned and long-term or permanently displayed work. At the privately owned yet sometimes publicly open Gibbs Farm, of twenty-nine major artworks only 10 percent are by women. There are more artists there named Richard and Peter than there are women, giving rise to a potential art Dick Index in the same vein as the John Index, which reflects the dominance of men on company boards. Other contemporary collections conform to the norm, with the proportion of female artists ranging from one third to none at all: Brick Bay Sculpture Park, 33 percent; Connells Bay Sculpture Park, 25 percent; Auckland City Council public art collection, 28 percent; Tai Tapu, Te Waipounamu South Island, 27 percent; Auckland Botanic Gardens, 24 percent; Wellington Sculpture Trust, 18.5 percent; SCAPE Public Art, 15 percent; and at the international gateway Auckland Airport Sculpture Park, 0 percent. As if ruling with an iron fist, a giant sculpture of a male hand recently crossed the country from Ōtautahi Christchurch to Pōneke Wellington, from one public city art institution rooftop to another, a not-so-subtle reminder of who has a firm grip on public space.

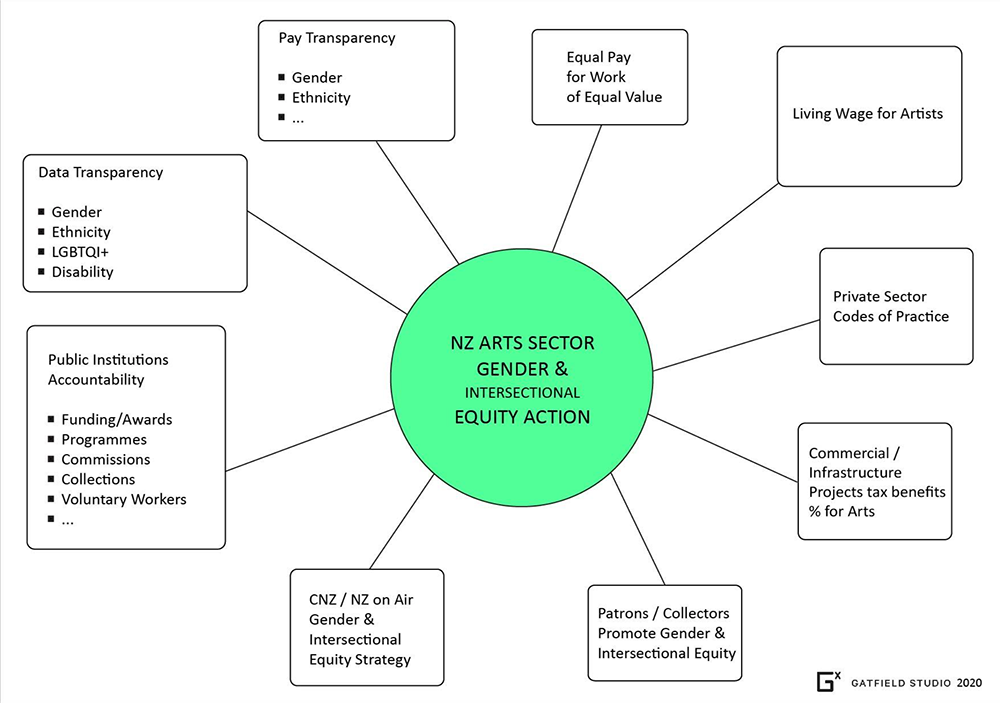

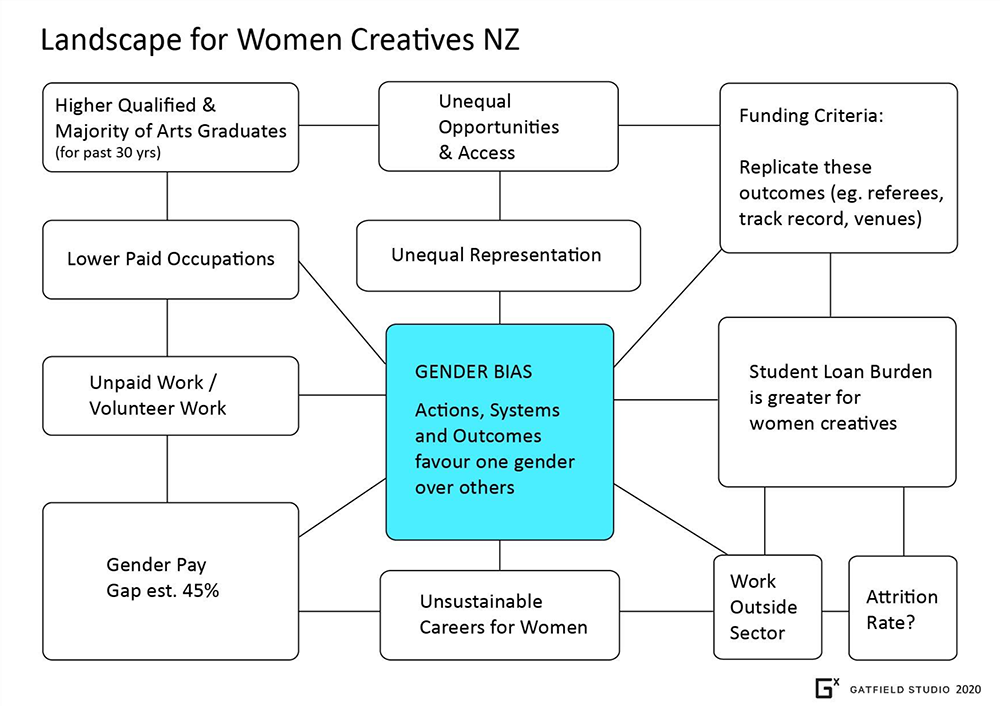

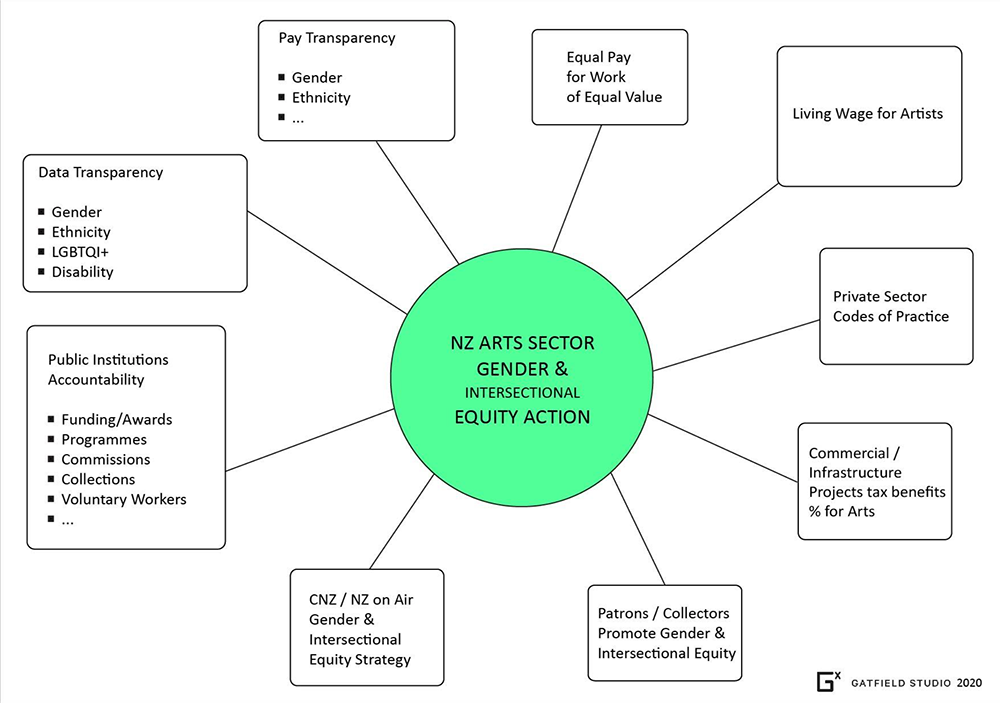

A deeply engrained culture of racial and gender bias runs through our historic monuments and in the under-representation of diverse figures and artists’ work in public space. Decade upon decade, incrementally, it all adds up. Token gestures and waiting for more time to pass will not correct the imbalance, especially during a pandemic where economic and social impacts fall more heavily on women and ethnic minority groups. None of this points to a conspiracy, but turning a blind eye in the face of knowledge is effectively an act of endorsement. It is time to get even, and assess whether ‘even’ is the right goal for gender diversity given the higher proportion of women artists who have graduated in the creative sector over the past thirty years. It’s time for proactive public art plans that honour the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi and deliver gender, racial and intersectional diversity. It’s time for an unbiased and inclusive public sphere.

Femisphere 4

Gill Gatfield

Inclusive Monuments

Under the crystallising lens of #BlackLivesMatter, the false histories and trauma embedded in our colonial monuments are unfolding. Shadows cast by statues of glorified ‘founding fathers’ stain the ground, unravelling a legacy of oppression, exploitation and violent conquest. Challenges and calls to review and replace these symbols need a plan of action, not only with regard to the promises of Te Tiriti o Waitangi but also under the gender spotlights of #TimesUp and #MeToo.

Women in Aotearoa have protested female exclusion from the public realm since colonisation began – from being denied the legal rights of ‘a person’ in the late nineteenth century, including the right to vote, to objecting to an overarching male symbolism in public space. In the context of a then new 1977 law promising equal rights for women, Māori and other marginalised groups, Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu, when opening the Waikato Savings Bank Building in Hamilton, pointed to the bank’s crest – “a Ram’s Head between two Bulls’ Heads,” and said:

May I suggest that it would be prudent –

in view of the Human Rights Commission Act …

if, on your shield at least one bull

were replaced by a cow.

Quotable New Zealand Women (Reed, 1994, np)

The Māori Queen’s quip made the connection between symbolism and human rights, and how these coexist in the public domain. Public cultural objects are powerful outward expressions of both the status of individuals and their values, and the state of equality in a nation or place.

Elevated notions of power and commercial value attach to masculine symbols, giving reason to a bank’s choice of rams and bulls. This translated into a University of Auckland Master of Fine Arts Painting Reader, a compilation of recommended texts – 90 percent penned by men, and almost exclusively about man-made art. On the cover, a tongue-in-cheek yet salient script from a John Baldessari painting Tips for Artists (1967-68):

Tips For Artists Who Want To Sell

…

Subject Matter is Important: It has been said that paintings with cows and hens in them collect dust … while the same paintings with bulls and roosters sell.

From paintings to sculptures, the bull reigns supreme – presiding over the pavements of Wall Street and mounted on countless pedestals. In a textbook mise en scène, Kristen Visbal’s Fearless Girl faced off with Arturo Di Modica’s Charging Bull in Manhattan for one year before being removed to stand alone, amidst complaints the Girl was a commercial ploy and faux feminism, detracting meaning and attention from the bull – itself a symbol of capitalism and full-frontal masculinity.

Across Aotearoa, a parade of colonial male muscle occupies pedestals and parks. Commemorated British-born politicians and leaders include those who orchestrated or led invasions of Māori pā and mana whenua, upheld the oppression of Māori and profited from stolen land. Among these ‘founding fathers’ are abusers and oppressors of women, and political leaders who repeatedly undermined women’s efforts to win the right to vote and used their power to deny New Zealand women the basic human rights.

In the nation’s capital alone, there are over 150 pieces of public art. Of the eighteen figurative statues, only two honour individual women – the colonial British monarch Queen Victoria and New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield. Only one Māori female figure stands in Pōneke Wellington, featured in the sculpture Hinerangi by Māori arts leader and artist Darcy Nicholas QSO, at Pukeahu National War Memorial Park. At a televised election debate between women party leaders in 2020, political promises were made to install one more monument in the Capital, honouring an otherwise absent nineteenth century Pākehā suffragist leader, Kate Sheppard.

Two memorials in Pōneke Wellington honour the British brothers William and Edward Gibbon Wakefield. They were imprisoned in England for abducting a 15-year-old girl from her school and forcing her into marriage for a ransom; a precursor to their exploits leading the New Zealand Company, a government-sanctioned enterprise that amassed and on-sold Māori land. In the Octagon at Ōtepoti Dunedin, a UNESCO City of Literature, a monument to Scottish bard Robbie Burns celebrates a sexual predator outed by poet Liz Lochhead in 2018 as Weinsteinian.

On the forecourt of Parliament, a larger-than-life Premier Richard Seddon, who actively obstructed women’s suffrage for years, stands centre stage. A 2020 #DitchDick campaign demands the statue’s removal, listing Seddon’s “opposition to women’s rights, promotion of racist policy against Chinese people, support for widespread confiscations and coercive purchase of Māori land, and attempts to invade and annex the Pacific nations of Fiji, Sāmoa and the Cook Islands, succeeding in the latter.” This is streets away from the narrative on the capital city’s official website asserting the Seddon statue “importantly injects a degree of humanity into the grounds, reinforcing the idea that Government is made of the people.”

As hidden histories emerge, how can we explain and elevate these figures’ contributions above their culpability for causing systemic and/or serious harm? If public art has power to engage human hearts, minds and spirits, then today those monuments serve only to reinforce and create further intergenerational harm. Caption rewriting cannot remedy or mitigate the cruel psychology of a glorified oppressor’s presence in public space. Such monuments belong in the Oppression Wing of an Aotearoa Museum for Women, with a shared boundary to the larger Museum of Racial Injustice – two containers for relics of a past for which there is no place in the present.

New monuments are needed of ancestors, activists and wāhine toa. The National Council of Women listed eight women worthy of a statue in the capital:

Meri Te Tai Mangakāhia – women's suffrage leader

Kate Sheppard – women's suffrage leader

Dame Whina Cooper – Māori women's activist

Princess Te Puea Herangi – Kīngitanga movement leader

Jean Batten – aviator and first person to fly solo from England to New Zealand

Kate Edger – first woman in New Zealand to gain a university degree

Whetu Tirikatene-Sullivan – long-serving MP

Elizabeth McCombs – first woman elected to parliament in New Zealand

There are many more.

A 2020 survey of 500 Māori generated a list of figures who inspired and created, including advocates, navigators, gardeners and tohunga. Tomorrow’s monuments might also honour the scientists, health-care workers, volunteers and essential services confronting Covid-19. Future monuments need not be limited to representing history and human aspiration in figure form. As Leonie Hayden (The Spinoff’s Ātea Editor) says, “What about monuments to generosity? To creation?” The project of democratising public space will allow and celebrate a refreshing diversity of expression and thought.

Attention also needs to be directed toward the commissioning process and the makers of public art. With rare exceptions (typically only when a woman is commissioned to make a statue or memorial for a woman), our public art makers are predominantly European and Pākehā men. The curated spaces of public sculpture exhibitions and sculpture parks reveal the particular function they play in creating the conditions that enable male artists to sustain a practice and to engage in public art.

At the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art Sculpture Park in Denmark, a permanent survey of international modern and contemporary work is listed among ‘The World’s Best Open-Air Museums.’ In 2015, I studied these works in what one commentator described as “all the modern masters of the art of sculpture,” and wrote in Art News New Zealand: “There’s no work by women artists in the Louisiana Sculpture Park, yet.” Five years later, there are still no women sculptors in this important collection.

In 2019, at the iconic Storm King, in upstate New York, one of the largest collections of outdoor sculpture in the world, I counted eighty-two artists in the permanent collection including long-term loans. Only fifteen of the artists were women – 18 percent. Beside Ursula von Rydingsvard’s Luba, in fading light, I staged a virtual Native Tongue, the alter ego of an ancient kauri sculpture: literally an Other I. The ephemeral companion momentarily nudged the proportion of women artists up closer to 20 percent. Numbers and pronouns are political. What’s measured, counts.

Gill Gatfield, Storm Queen, 2019.

(Native Tongue AR, 2018, with Ursula von Rydingsvard, Luba, 2009–10, at Storm King, New York)

Male occupation of public space is measured also through the pages of academia. Amazon recently delivered a much anticipated new book – Abstraction Matters: Contemporary Sculptors in Their Own Words (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019). The text expounds on the ideas of fourteen sculptors, including current practitioners, selected for being “not only eminent artists who made their mark in the contemporary sculptural landscape: they are also sharp and insightful theorists, inclined to reflect intensely upon the sense of their own work in particular and upon the nature of abstract sculpture in general.” The sculptors in Abstraction Matters are all men. The project demarcates a paradigm in which the makers’ heroic work and texts define the canon. There is literally no room for the Other. As a practitioner of abstraction, I sawed the book in half.

There’s no shortage of women contenders for sculpture books, parks and public collections. Smart public bodies like the UK Arts Council acquired 250 sculptures and installations by more than 150 women, across seventy-five years, including ‘ambitious work’ – the content for a major 2020 touring show in the UK, Breaking the Mould: Sculpture by Women Since 1945. In Los Angeles, Hauser Wirth & Schimmel’s exhibition Revolution in the Making: Abstract Sculpture by Women, 1947–2016 presented 100 works by thirty-four international women artists, tracing ways in which women have “changed the course of art by deftly transforming the language of sculpture since the post-war period.”

I think of Anni Albers, who was prevented from studying architecture at the Bauhaus, and directed instead to learn weaving, as “women were unsuited to the rigours of geometry.” Not content with her allocated art form being demoted to second rate, Albers disrupted that canon and built walls of fabric.

Gill Gatfield, Get Even – Abstraction Matters, 2020

Cities and sculpture exhibitions and parks in Aotearoa bulge with old and new artworks by male artists. Where doors are open, female artists demonstrate innovation, capacity and experience in making outdoor public work, and present challenging works in large numbers in successive national exhibitions such as the NZ Sculpture OnShore, a Women’s Refuge fundraiser, in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. Signs of a glass ceiling surface in the commissioning of permanent public work, and in the numbers of female artists shrinking as the prestige of a sculpture exhibition and the rewards on offer increase. At the ratepayer- and patron-funded biannual Auckland Botanic Gardens Sculpture in the Gardens 2015–2016, less than one quarter of artists selected were women (24 percent). Similarly in the biannual exhibition headland Sculpture on the Gulf 2017, women artists made up just over one quarter of those selected (27.5 percent).

These numbers are reflected in the gender-skewed picture of commissioned and long-term or permanently displayed work. At the privately owned yet sometimes publicly open Gibbs Farm, of twenty-nine major artworks only 10 percent are by women. There are more artists there named Richard and Peter than there are women, giving rise to a potential art Dick Index in the same vein as the John Index, which reflects the dominance of men on company boards. Other contemporary collections conform to the norm, with the proportion of female artists ranging from one third to none at all: Brick Bay Sculpture Park, 33 percent; Connells Bay Sculpture Park, 25 percent; Auckland City Council public art collection, 28 percent; Tai Tapu, Te Waipounamu South Island, 27 percent; Auckland Botanic Gardens, 24 percent; Wellington Sculpture Trust, 18.5 percent; SCAPE Public Art, 15 percent; and at the international gateway Auckland Airport Sculpture Park, 0 percent. As if ruling with an iron fist, a giant sculpture of a male hand recently crossed the country from Ōtautahi Christchurch to Pōneke Wellington, from one public city art institution rooftop to another, a not-so-subtle reminder of who has a firm grip on public space.

A deeply engrained culture of racial and gender bias runs through our historic monuments and in the under-representation of diverse figures and artists’ work in public space. Decade upon decade, incrementally, it all adds up. Token gestures and waiting for more time to pass will not correct the imbalance, especially during a pandemic where economic and social impacts fall more heavily on women and ethnic minority groups. None of this points to a conspiracy, but turning a blind eye in the face of knowledge is effectively an act of endorsement. It is time to get even, and assess whether ‘even’ is the right goal for gender diversity given the higher proportion of women artists who have graduated in the creative sector over the past thirty years. It’s time for proactive public art plans that honour the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi and deliver gender, racial and intersectional diversity. It’s time for an unbiased and inclusive public sphere.

Femisphere 4

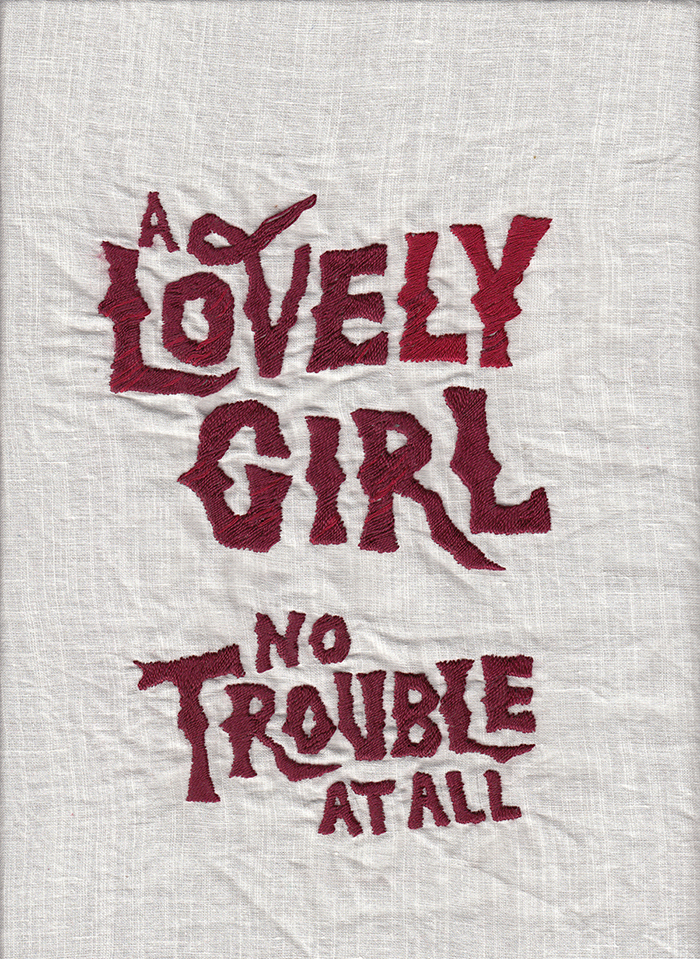

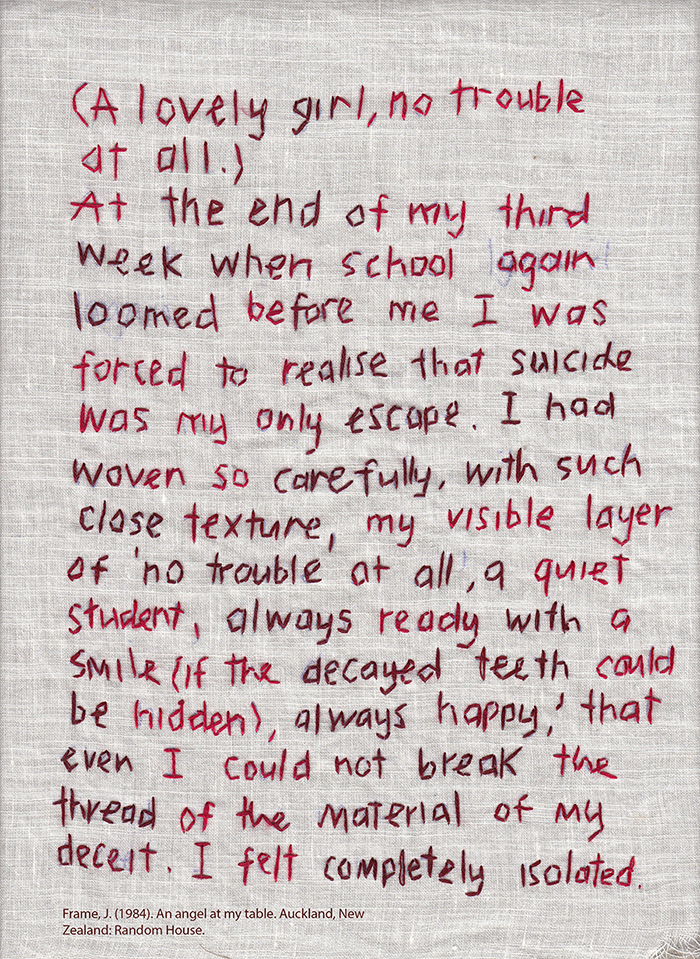

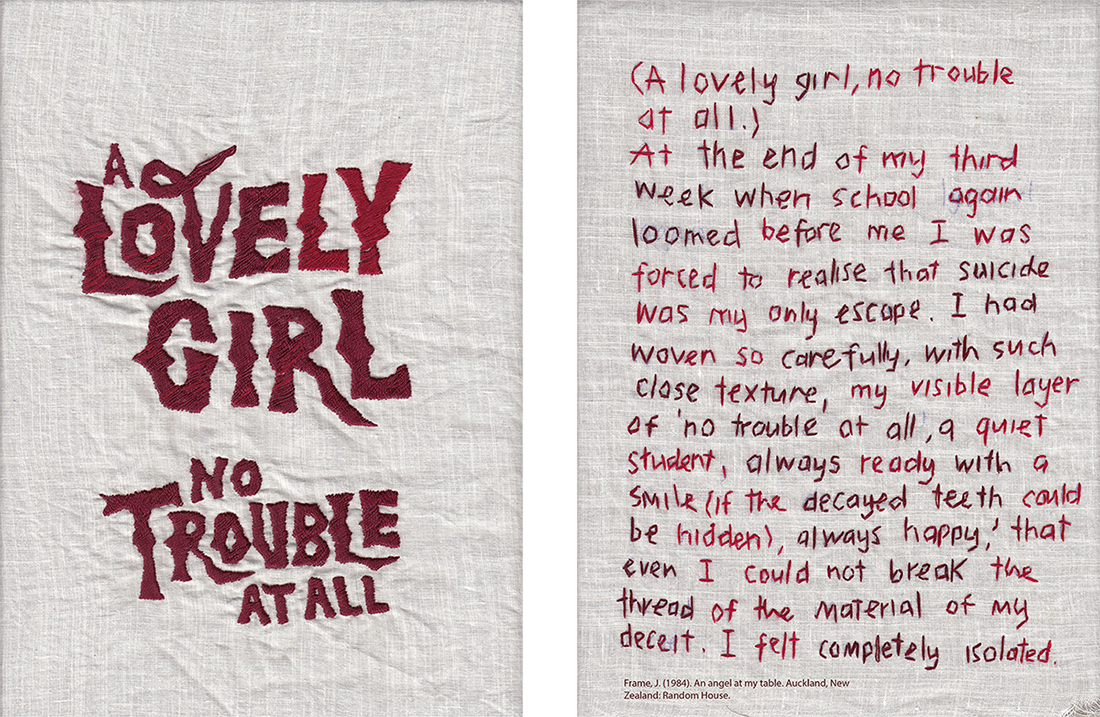

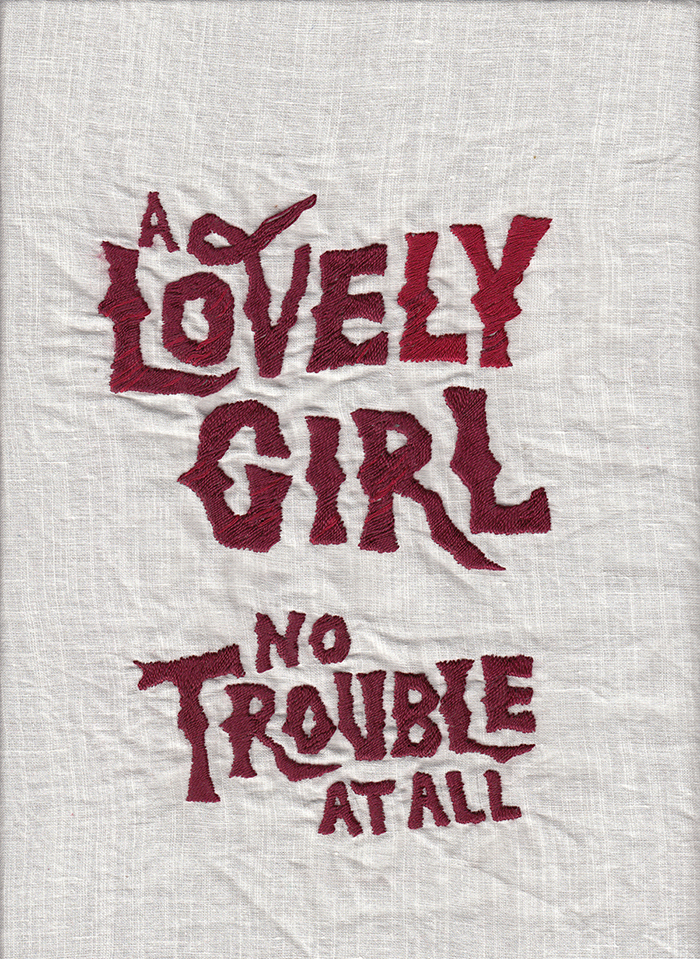

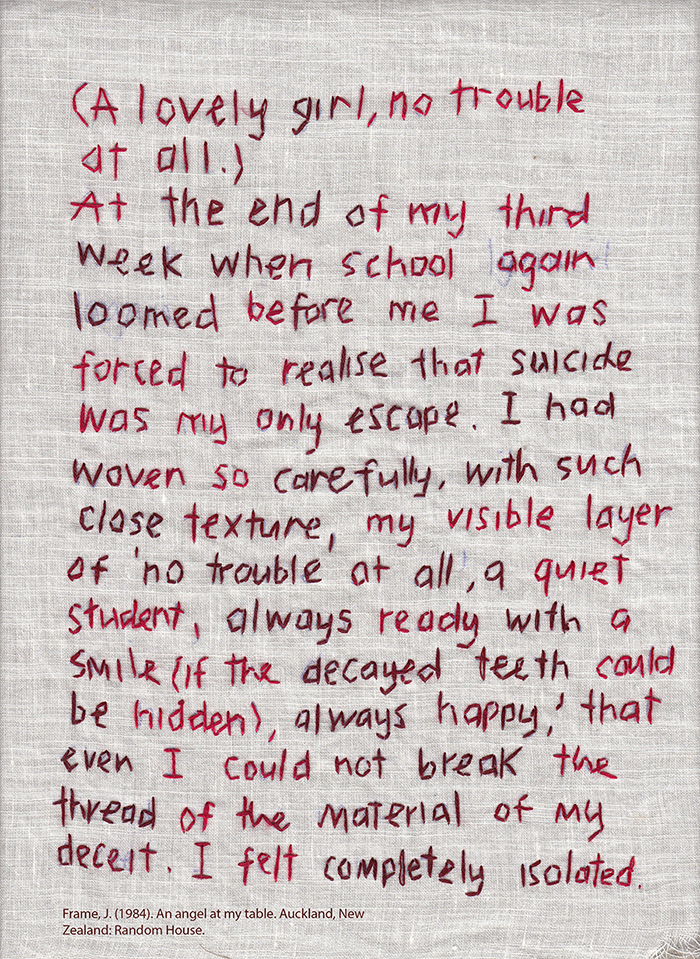

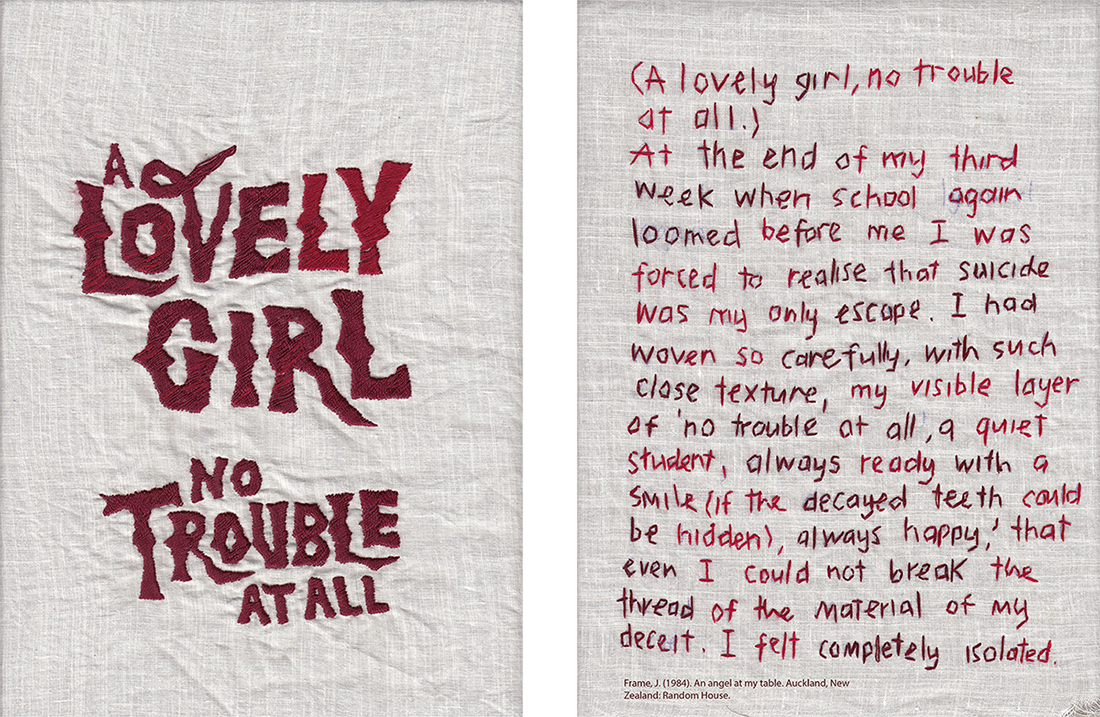

Alice Alva

Femisphere 4

Alice Alva

Femisphere 4

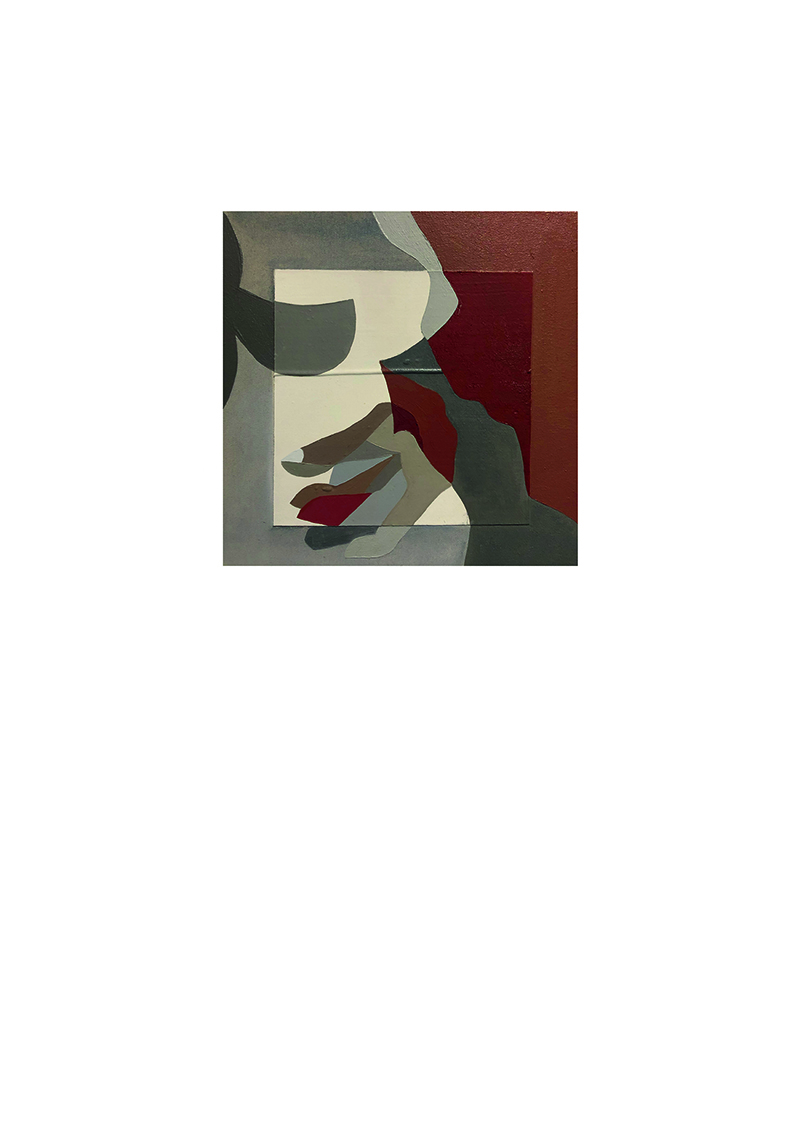

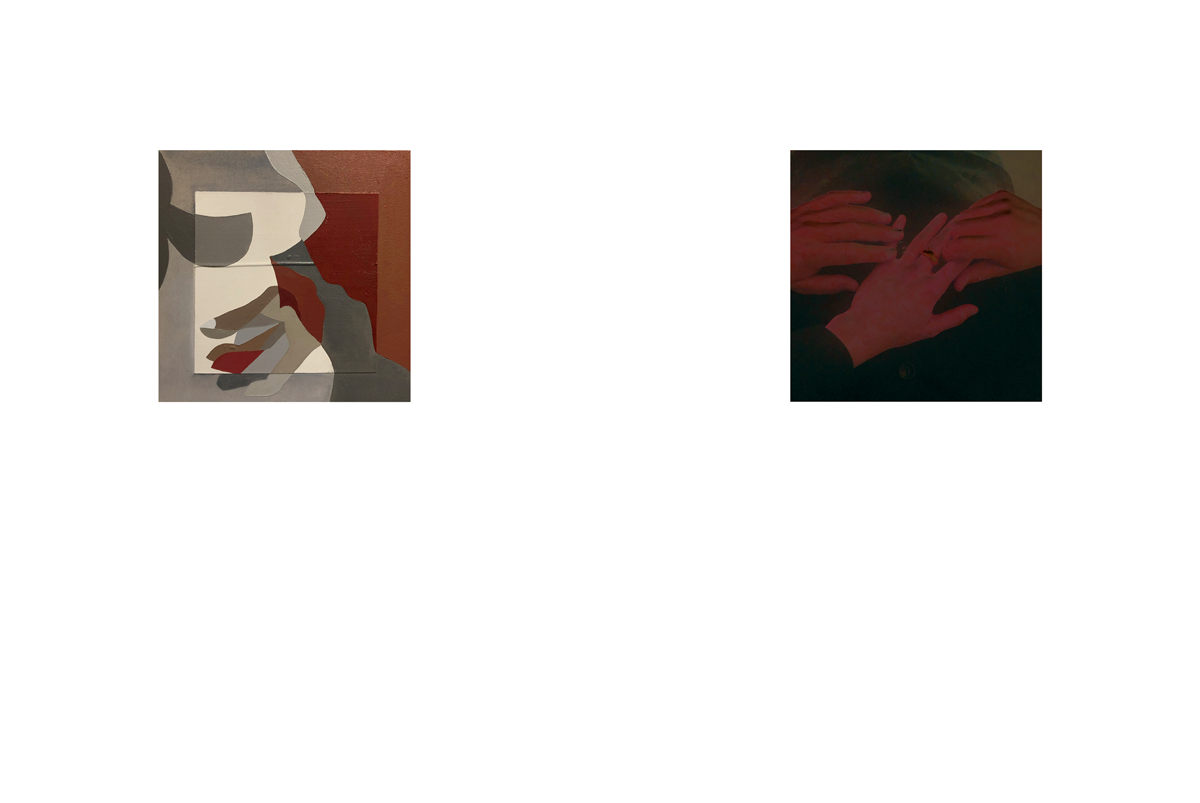

Grace Bader

Femisphere 4

Grace Bader

Femisphere 4

Lisa Crowley

Lisa Crowley, Life Seen by Life (stills), 2019, digital scans from 16mm film.

Text excerpt from Agua Viva, by Clarice Lispector.

Femisphere 4

Lisa Crowley

Lisa Crowley, Life Seen by Life (stills), 2019, digital scans from 16mm film.

Text excerpt from Agua Viva, by Clarice Lispector.

Femisphere 4

Jen Bowmast & Priscilla Howe

Femisphere 4

Jen Bowmast & Priscilla Howe

Femisphere 4

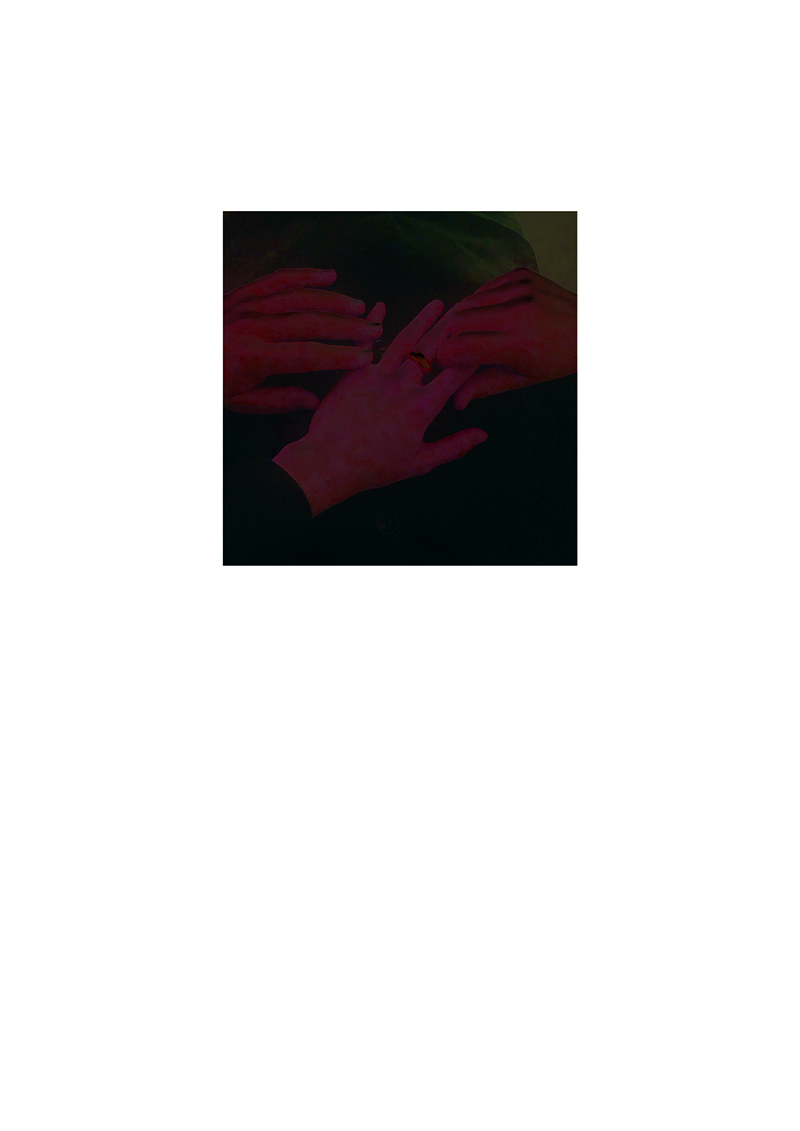

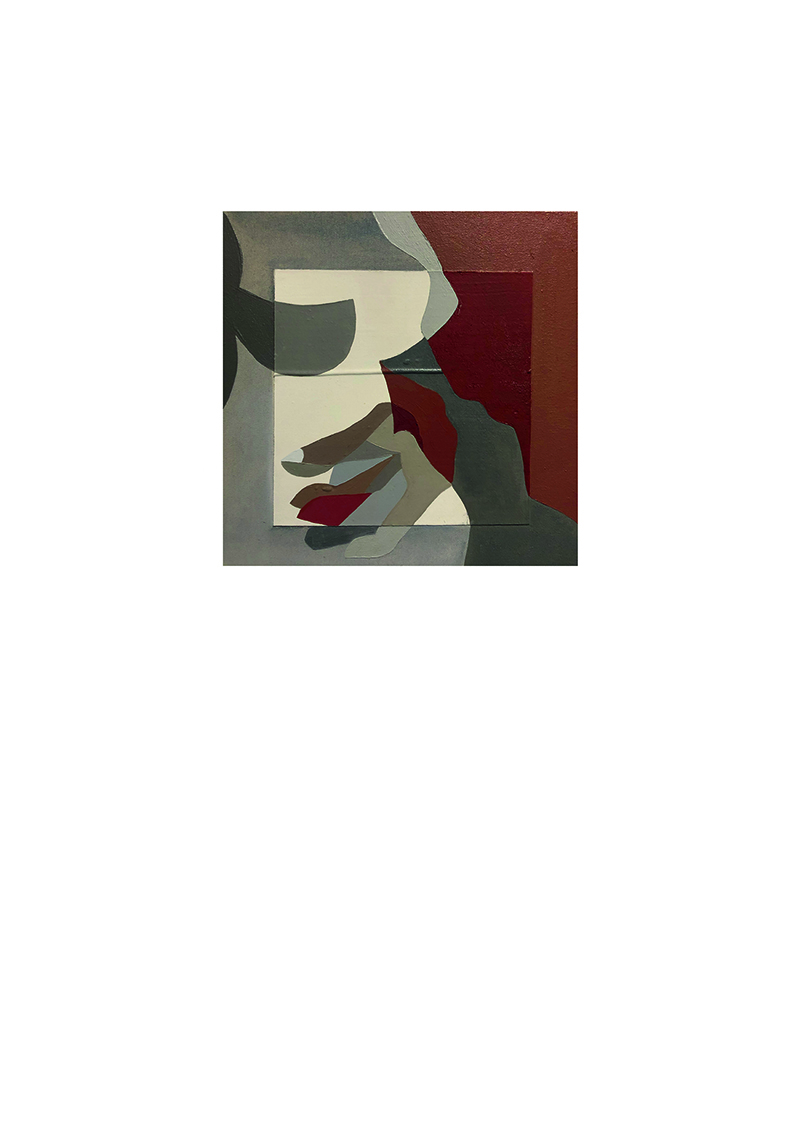

Greta Anderson

Guru Gurl

“I encountered the female guru as an adult,” admits Greta Anderson. “The gurus were always male, until I noticed a female guru on my GP's office wall. Her name is Gurumayi Chidvilasananda.”

“The folk around me growing up were Western Indophiles. Guru culture was something I experienced on the commune [as a young person]. As a child I thought they were silly and weird. [Now], as an adult, I know them to be sometimes useful and other times abusive.”

Anderson’s latest body of work circles around the idea of suburban gurus – ones who, when removed from their ashram-style commune context, she speculates might have another role. What if a guru doesn’t lead us to enlightenment, but to infantile narcissism? Psychology lecturer Steve Taylor talks about a ‘guru syndrome,’ in which followers, “may feel a sense of oneness or bliss in the company of the guru, but this isn’t genuine enlightenment. It's more akin to the sense of oneness that a baby feels with their mother.”

This new series, still in the making, is called The Transcenders. The gender of this guru in the physician’s office struck a chord. All of the portraits in this series are of women. They pose with weirdly glowing props in a spot-lit arena. The women in these photographs span a range of life stages. They stand or sit purposefully alone; their intensity is inexplicably potent.

Continuing to use the day-for-night techniques she has used in earlier series, she produces high-contrast images that throw any background into a velvety, shadowy blackness. Her images are single-object portraits. Her subjects, whether houses, people or props, are positioned in the centre of the picture plane, heavily lit, all else darkened. The subjects are, like the guru outside of the commune, stripped of context.

The high shine, intense focus and stripped-back aesthetic all suggest the artistic equivalent of a hard stare at the trappings of new-age lifestyle. They steel us against a regression to a childlike state of irresponsibility and unconditional devotion to our spiritual teachers.

Her portrait sitters are stand-ins. “I shoot people I know. My students, friends, etc. I have done a series of men, too; for example, I shoot repair men that come to my house.” This prosaic fact recalls a much earlier body of work called The Stand-Ins, in which Anderson explored the idea of a person, place or object being a psychic or symbolic marker. Weeds, for example, are stand-ins for indigenous, displaced flora. These subtle symbolic codes are what give Anderson’s works their tension and staying power. Her residential dwellings, spot-lit and caught in an artificial twilight, might imply a concealed site of cult-led trauma, or they might simply be goading at suburban Aotearoa’s vernacular housing. Anderson’s hard stare is a point of pause, a cautionary tale, in which to stand and question as well as worship.

Hanna Scott

Femisphere 4

Greta Anderson

Guru Gurl

“I encountered the female guru as an adult,” admits Greta Anderson. “The gurus were always male, until I noticed a female guru on my GP's office wall. Her name is Gurumayi Chidvilasananda.”

“The folk around me growing up were Western Indophiles. Guru culture was something I experienced on the commune [as a young person]. As a child I thought they were silly and weird. [Now], as an adult, I know them to be sometimes useful and other times abusive.”

Anderson’s latest body of work circles around the idea of suburban gurus – ones who, when removed from their ashram-style commune context, she speculates might have another role. What if a guru doesn’t lead us to enlightenment, but to infantile narcissism? Psychology lecturer Steve Taylor talks about a ‘guru syndrome,’ in which followers, “may feel a sense of oneness or bliss in the company of the guru, but this isn’t genuine enlightenment. It's more akin to the sense of oneness that a baby feels with their mother.”

This new series, still in the making, is called The Transcenders. The gender of this guru in the physician’s office struck a chord. All of the portraits in this series are of women. They pose with weirdly glowing props in a spot-lit arena. The women in these photographs span a range of life stages. They stand or sit purposefully alone; their intensity is inexplicably potent.

Continuing to use the day-for-night techniques she has used in earlier series, she produces high-contrast images that throw any background into a velvety, shadowy blackness. Her images are single-object portraits. Her subjects, whether houses, people or props, are positioned in the centre of the picture plane, heavily lit, all else darkened. The subjects are, like the guru outside of the commune, stripped of context.

The high shine, intense focus and stripped-back aesthetic all suggest the artistic equivalent of a hard stare at the trappings of new-age lifestyle. They steel us against a regression to a childlike state of irresponsibility and unconditional devotion to our spiritual teachers.

Her portrait sitters are stand-ins. “I shoot people I know. My students, friends, etc. I have done a series of men, too; for example, I shoot repair men that come to my house.” This prosaic fact recalls a much earlier body of work called The Stand-Ins, in which Anderson explored the idea of a person, place or object being a psychic or symbolic marker. Weeds, for example, are stand-ins for indigenous, displaced flora. These subtle symbolic codes are what give Anderson’s works their tension and staying power. Her residential dwellings, spot-lit and caught in an artificial twilight, might imply a concealed site of cult-led trauma, or they might simply be goading at suburban Aotearoa’s vernacular housing. Anderson’s hard stare is a point of pause, a cautionary tale, in which to stand and question as well as worship.

Hanna Scott

Femisphere 4

Ali Senescall

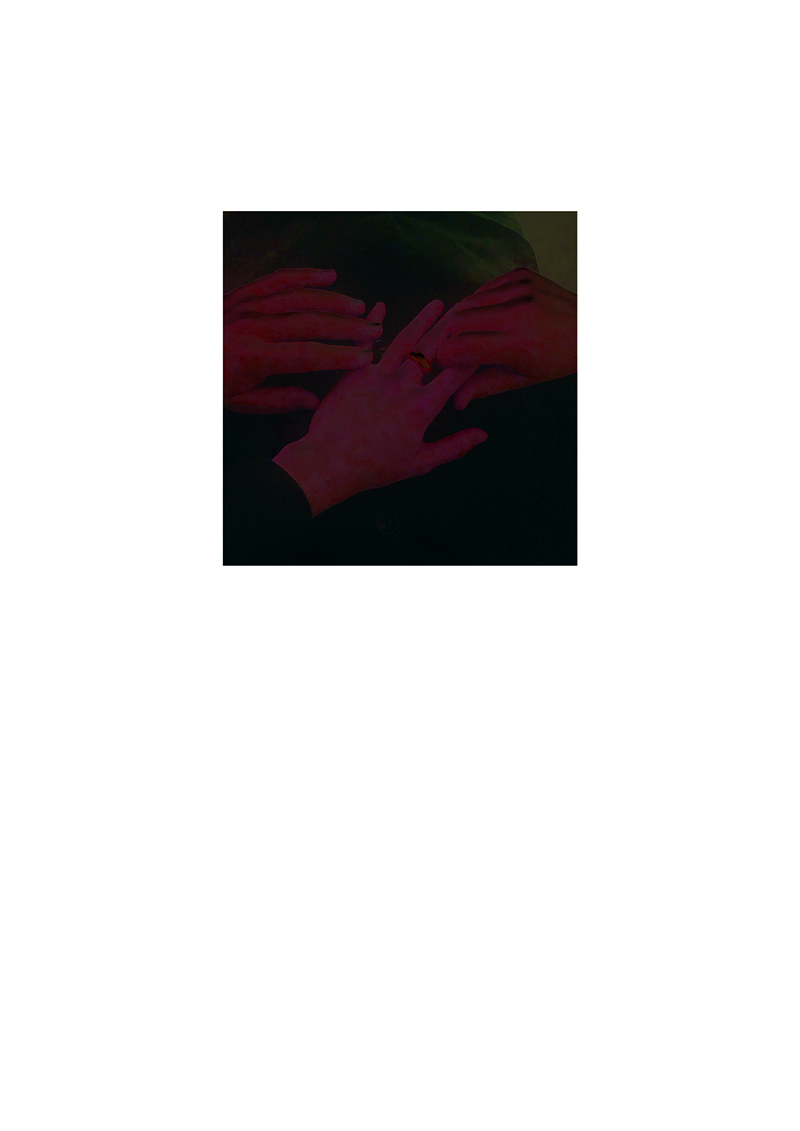

Ali Senescall, The Piano Teacher, 2020

Femisphere 4

Ali Senescall

Ali Senescall, The Piano Teacher, 2020

Femisphere 4

Teresa Peters

Ode To Mother (Earthed)

all lines

converge

at the centre

not the middle

but

just outside

the picture...

Joanna Margaret Paul, “O, Seacliff,” June 1973 (excerpt)1

Made from the same clay. Mother and daughter Maree Horner and Teresa Peters both explore embodiment within our respective practices. My current practice is based in clay and ceramics – bodies that echo the prehistoric. Maree currently works in graphic, body-scale multimedia works that are monolithic testaments to the female. These works often juxtapose and dwarf glorified monuments of culture with domestic objects, a complex interplay of the familiar and the erotic. Stemming from Familiar Monuments (1996), the archaeology of the ideas can be traced back to Chair (1973).

Maree Horner, Chair, 1973

In the 1970s Horner became known for sculptural works that demonstrated a sensitivity of material and form. These works included precarious glass constructions, ice monoliths, and one work consisting of an electrified domestic armchair. In Chair (1973) Maree Horner harnesses pure electricity in a work that is made to shock.

A current pulses through the chair, while the floor is only for earthing and could be walked onto. The piece is very silent except for a quiet continuous tick, tick. I was thinking about suburban neurosis and the person who sits in a comfortable chair and doesn't think about anything. In order to keep the cats off, my father used to electrify his car every night with a battery and an electric fence unit like I used in the chair. I liked that idea and that image. 2

Maree Horner was a female forerunner in the development of conceptual and post-object art in New Zealand. In Groundswell: Avant-Garde Auckland 1971–79 at Auckland Art Gallery, 2018, Maree Horner and Fiona Clark stood as the two women innovators in the energetic movement that crossed institutional lines, embracing raw energy – performance, site-specific and land art.

Teresa Peters, ECHO BONE, 2019

In 2020 my ceramics are interested in bodies. Earth bodies, forming and transforming. Chemical compounds and molten entities, in intimate combustion. These raw clay and ceramic installations are interested in rhizomic multiplicity, nomadic transformation and the tentacular. Merging biomorphic and anthropomorphic forms in a poetry of touch. Ceramics is alchemy. Earth, water, air… fire. ECHO BONE (2019) “excavates primordial totems,” as we move through the Anthropocene, the epoch in which human activity took dominant effect on the environment. Navigating fetish and value in times of late capitalism and environmental dystopia. Looking to destroy categories and knock art off its pedestal, while exploring expanded fields and new understandings of environment.

Maree Horner’s 1970s work has been retrospectively celebrated manyfold in the last years. In 2019 Chair was reconstructed and exhibited at Anderson Rhodes Gallery, New Plymouth. Diving Board (1973–98) showed in 2016–17 as part of All Lines Converge and in 2019 as part of Ruth Buchanan’s The scene in which I find myself / Or, where does my body belong, both at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. On the show’s Gallery 3 mezzanine, categorised under Exception and Politics, Maree Horner’s Diving Board and Judy Darragh’s Wild Thing (1999) flank the space. They represent as two of the godmothers of New Zealand Her-story. Ruth Buchanan’s conversation utilises the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery’s collection as it seeks to embody, and at the same time dissect, the art canon.

The disproportionate under-representation of women, Māori, Pacific, and other minority artists is absolute. Here, the friction comes to life as various positions meet, squeezing up against each other and moving toward something that more closely represents our pulsating bodies. This new entity is not perfect, not flawless, not even really free, but made of bodies nonetheless, multi-layered, expansive, where skin, bone, flesh, and the diagonal forces in motion that keep us together come to the fore. Through this operation what is produced is – as American poet and activist Audre Lorde has described – a scrutiny that is intimate.

Maree Horner and Teresa Peters look to the body and earth bodies to subvert monumental paradigms. “Locating power automatically snaps to how bodies, languages, and architectures navigate, exaggerate, scramble, or reconstruct how power looks and is experienced.” As a pandemic embodies our civilisation, grinding the human institution to its ass, let us give ode to the foremothers who have fought the revolutions before us so we now can continue to evolve in power. Earthed.

1. Joanna Margaret Paul, “O, Seacliff,” June 1973 [excerpt], in All Lines Converge [exhibition guide] (New Plymouth: Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, 2017).